La Scuola Grande di San Giovanni Evangelista, fondata nel 1261 a Venezia, è la più antica fra quelle ancora funzionanti sul territorio della città. La Scuola, una delle più ricche e prestigiose, era una corporazione di Battuti che riuniva attorno a sé la devozione per il proprio santo patrono. Nel corso dei secoli la sede fu ristrutturata, ampliata ed impreziosita con opere d’arte che la rendono uno dei complessi più belli e monumentali di Venezia, frutto di molti decenni di abbellimenti architettonici e decorativi di immenso valore artistico. Nel Museo d’Arte di Cleveland è conservato il frontespizio della Mariegola della Scuola di San Giovanni Evangelista, un libro di regole o statuti destinato a regolare le attività dei membri della confraternita. È essenzialmente la prima pagina splendidamente decorata di un manoscritto risante agli anni tra il 1300 e il 1330, appartenuto alla confraternita di San Giovanni Evangelista.

The oldest among the five Scuole Grandi of Venice is the Scuola di San Giovanni Evangelista, founded in 1261. This institution is considered one of Venice’s most beautiful and monumental complexes, rich in works of art and architecture. A narrative of many important moments in the city’s rich history is revealed by the variety of different spaces within the Great School of St. John the Evangelist, a result of several centuries’ worth of architectural and decorative embellishments of immense artistic value. Here, visitors may witness a visual dialogue among the Middle Ages, Renaissance and the 18th century through the school’s interior and exterior spaces.

The term Scuola, meaning “School,” was used by the ancient Republic of Venice to identify a confraternity, brotherhood or group of lay citizens who dedicated themselves to their mutual material and spiritual assistance and who practiced in honor of the patron saint of that school. The focus of this Christian confraternity was especially on commemoration of the dead and prayers for the living. During the late Middle Ages, most Italian towns had one or more confraternities, organizations of lay people who undertook to carry out the ideals of religious orders such as the Franciscans or Dominicans. Confraternities were created for the special veneration of a saint or the Holy Sacrament. One of their tasks was to strengthen the faith of their members in addition to undertaking charitable work.

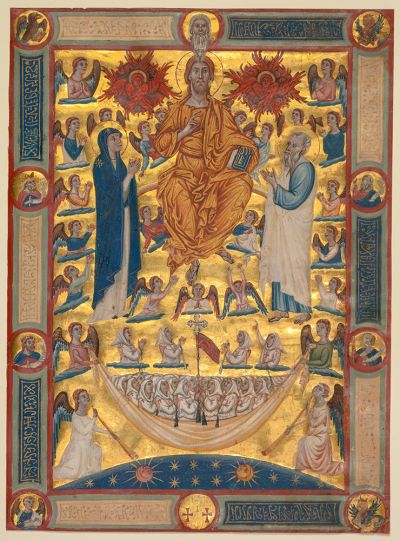

In the Cleveland Museum of Art is preserved the frontispiece of the Mariegola of the Scuola di San Giovanni Evangelista. It is essentially an elaborate and beautifully-decorated first page from a manuscript dated between 1300 and1330 that once belonged to the confraternity of St. John the Evangelist. This beautiful page was intended to visually introduce the mariegola, or book of rules or statutes, meant to govern members of the confraternity. A depiction of the Last Judgment is set against an ornate gold background with every figure dressed in vibrant garments that seem to glow. Christ is seated in the center with the sign of benediction. To the viewer’s left is the Virgin Mary, clad in her traditional blue robe and to the right is Saint John the Evangelist. They both signal and look up towards Christ, emphasizing where the viewer’s attention should be. Many angels, all of who stare devotedly up at Christ, flank the three main figures. In the bottom third of the page is a crowd of hooded figures, members of the Scuola di San Giovanni Evangelista, the commissioners of the page. They all bear the same red cross and insignia of their order on their robes and their hoods cover their heads. From their clasped hands hangs the traditional whip used for self-flagellation rituals that occurred within many of the medieval confraternities in Italy. They stand in a tightknit group and some are fully blocked by those in front. It was not uncommon in the 1300s for confraternities to commission works such as this and group members would often be included in the images. The imagery from the frontispiece now in Cleveland symbolizes the confraternity’s ideals of brotherhood and emphasizes the importance of both the collective group as well as the importance of keeping their individual anonymity.

The headquarters of these Christian confraternities held relics, vestments, decorations, small sculptures, and other religious objects that were carried or displayed on the day of the patron saint’s procession or on religious and public holidays. The confraternity building in the San Polo sestiere features numerous architectural enhancements that were built over the centuries by renowned architects and decorated with the works of the finest artists of the time. A defining moment for the School of St. John the Evangelist was the donation of the Relic of the Cross (1369), which became the symbol of the School and the object of an extraordinary veneration. Due to its increasing devotional and economic importance, the structure of the confraternity building gradually expanded.

An impressive series of paintings dedicated to the Miracles of the Cross was commissioned at the end of the 15th century from Vittore Carpaccio, Gentile Bellini and others. The paintings, now preserved at the Accademia Gallery in Venice, further enriched the decoration of the Oratory of the Cross. A painting from the mid-1500s by Titian that once decorated the ceiling of the Hall of the Lodge (now in the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.), was the starting point of a rich iconographic program of the Apocalypse. The latest significant and radical architectural changes to the building were those of the 18th century for the Chapter Room, a place intended to accommodate the general meeting of the members, which took place between 1727 and 1762 under the direction of Giorgio Massari. Massari was an architect of proven talent who created an environment of grandeur, both elegant and bright, with a magnificent colored marble floor. It was an absolute masterpiece in 1752 and remains so for today’s visitors. The majority of the paintings on the walls are by Domenico Tintoretto, which recount stories from the life of St. John the Evangelist according to the “Golden Legend” by Jacopo da Voragine.

On May 12, 1797, the ancient Republic of Venice ended and by Napoleonic decree in 1806, the School was abolished, became state property and was then sold. The once opulent rooms became warehouses and the confraternity’s works of art were expropriated. When the Austrians took over from the French, they even planned to demolish the confraternity building.

Fortunately, in 1856, Gaspare Biondetti Crovato, the building constructor from the Friuli region, with the aid of a group of Venetian citizens, raised enough funds to buy the Scuola from the Austrian State. It is today preserved as one of the great historic buildings of Venice where visitors may enjoy its cultural and architectural treasures. Cleveland’s leaf from the Scuola’s mariegiola is a small but tangible connection to its rich history.