The first night of our 1992 family reunion in Montelongo, my paternal grandparents' village, Zia Mariannina and Zia Rita locked the door and then barred it with a two-by-four. I looked at my mother. Was this a movie set of the lawless Old West? The elderly women did the same, with firm resolve, every night of our stay.

We questioned the aunts (they were really cousins, but their age dictated I call them aunts) about why such heavy security was necessary in such a peaceful Molisano village encircled by fields of sunflowers. Their answer was "briganti," brigands, roving gangs of robbers. A few months before, thieves had stolen from a church in a nearby town. Then there was another matter, much older and more traumatic. The Germans occupied Montelongo in the fall of 1943 and seized the house, turning it into a command post. The elderly aunts never discussed the war while we were there; my father related it to us back home in the U.S. The recent church looting and our Italian relatives' WWII experiences were just the first layers of nagging insecurity.

In an earlier stay in Montelongo, I once took the neighbor's hunting dog for a walk outside the village, close to the neighboring town of Santa Croce. I wanted a better look at the tall, ruined tower visible from the aunts' window in Montelongo. Upon approach, I saw large stones scattered, fallen from the crumbling structure. At one time, it must have reached at least four stories high. Unfortunately, no signs were posted indicating anything about the circular ruin. Back at the house, Mariannina told me that I had explored an ancient lookout, la Torre Di Magliano, the project of a local lord who designed it to protect against brigands menacing the area 800 years ago.

With further investigation done back home in Ohio, we learned that post-unification Italy had suffered an era of chaos when gangs of outlaws roamed the countryside in Molise as well as in the South and in Sicily. This territory encompassed the old Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, a Bourbon realm with its capital at Naples, a thriving city where thousands of workshops turned out luxury goods for Europe.

The new Kingdom of Italy was born in 1861, when Garibaldi handed the conquered Kingdom of the Two Sicilies to Victor Emmanuel II, the united country's first ruler. Unfortunately, the benefits that unification brought to Italy were not awarded equally to all regions. In Molise, the Abruzzi, and the Southern provinces, few of the expected benefits of a united Italy arrived. In fact, high taxes and rents financed the development of industry in the North. Not only was the old Bourbon kingdom now annexed to the rest of the boot, its banks were forced to hand over huge quantities of gold bouillon to the newly formed nation.

To make matters worse, many peasants lost their livelihoods as communal pastures and other public lands so necessary to small farmers' subsistence became private property. A sense of desperation settled over the Southern countryside as the hopes raised by unification quickly turned into resentment and rebellion. In fact, farmers and sharecroppers found themselves under an even heavier burden than they had experienced under the Bourbon king. Social disorder exploded in the old Kingdom of the Two Sicilies in 1869, in reaction to a gristmill tax that increased the price of bread. The situation became chaotic as many dispossessed peasants, men and women, and former soldiers of the Bourbon king took to looting in order to survive. It was the time of the briganti.

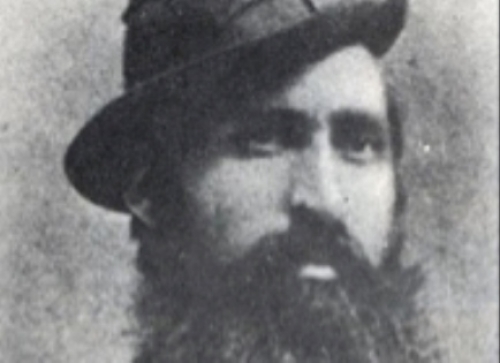

With the onset of extremely bad economic times, several bandit groups organized to take justice into their own hands, often pillaging and kidnapping along the way. In response, Victor Emmanuel II sent 100,000 troops to repress the rebellious territory. His soldiers killed thousands, among them many innocents. In the South, Carmine Crocco, one of the most notorious of the brigands, organized a guerrilla army of 2,000 to attack the new Kingdom of Italy. He often targeted the wealthy who had sided with the new government. Nonetheless, Crocco's Army and other brigands were a danger to public safety. People stayed inside, behind barred doors.

In the end, my U.S. family and I came to understand the nightly ritual of barring the doors in the paese. You see, the era of the brigands corresponded to the lifetimes of Mariannina and Rita's grandparents. Imagine the stories they must have heard as children! The watchtower, viewable from their house, was also a constant reminder of history. Then the shock of a sacred place recently robbed and a home once occupied in warâ yet two more. Every night before turning in, the aunts lifted not just a timber crossbar but with it at least eight centuries of Italian history.