Easter and its eggs

In Italy, eggs are traditionally presented as an Easter gift. Nowadays, "Easter eggs" are made of milk chocolate or dark chocolate and hide inside a small surprise for the youngest; however, in the past, they were simple eggs perhaps decorated with flowers and placed in a basket to be donated. While eggs embody the symbol of Christian rebirth, in reality Christianity borrowed such images from a variety of other sources. In fact, an egg has very ancient symbolic origins that developed over a long span of time and in different areas of the world.

It seems that the first nation to associate an egg with the celebration of Easter was Germany, where eggs were boiled first, then embellished with flowers and donated as an Easter gift; however, the symbolism of strong representative elements not associated with Easter has ancient origins as well; in Mesopotamia, for example, an egg was a symbol of life, and for pagan populations, it was a symbol of fertility and continuation of the Genesis. Ancient Romans used to say Omne vivum ex ovo, meaning "an entire life comes from an egg." The perfection of the egg’s circular shape itself was associated with the birth of everything. The practice of decorating and painting eggs as a good omen of birth originated with the Romans. Egyptians and Indians believed that the universe had been created by a large egg, and that the sky and the Earth were its two opposite ends. An egg was also associated with fertility rites. Even for the Chinese, the egg represented the perfection of the union between “Yin-Yang,” between “Earth and Heaven.” Even today, eggs are the symbol of a new spring season for Iranians and Greeks, and thus are gifted as a good wish for a new year. In Israel, they are a symbol of good luck, and customarily an egg is given to friends as a gift.

A Christian legend speaks of the miracle of the red eggs. It appears that while returning from the Holy Sepulcher before announcing the miracle of the resurrection of Christ to the disciples, Mary Magdalene came upon Peter, who did not believe the news, and said to her: “I will believe you only provided that the eggs you carry in your basket will turn red.” Legend says they did, and from then on the egg became a symbol of Christ’s resurrection from the grave to eternal life. Early Christians would celebrate Easter by donating eggs wrapped in leaves, while noble people used gold painted leaves. Today, children play with colored eggs on Easter Sunday. In Abruzzo, they also play a traditional game called “Mo 'chin latt,” in which each participant holds a hardboiled egg that taps against the others’. The winner is the child whose egg shell will remain intact. In France, Germany, and Austria, “egg picking” is a beloved game where competitors will let hard boiled eggs roll down a gentle hill, and the egg reaching the bottom with the fewer cracks will win the race. In Luxembourg, instead, each child is given a spoon with a boiled egg resting in it, and the child who will cross the finish line without letting the egg fall will be proclaimed winner.

Judging from this historical overview, we can conclude that the egg, thanks both to its spherical perfection as well as attribute as bearer of life, has always symbolized birth, rebirth, peace, and serenity throughout history. I wish you a happy Easter. May it be the best ever!

Pasqua e le sue uova

Per la Pasqua, in Italia, è buon uso regalare delle uova. Oggi le “uova di Pasqua” sono fatte di cioccolato al latte o fondente con il regalo all’interno per i più piccolini, ma in passato erano semplici uova magari ornate con qualche fiore ed inserite in un cesto per essere donate. L’uovo racchiude in sé il simbolo di rinascita cristiana, ma in realtà, la cristianità ha preso la rappresentazione dell’uovo da altre parti. L’uovo possiede in sé origini simboliche antichissime che si sono sviluppate in diverse epoche e in diverse località.

Pare che la Germania sia stato il primo paese ad aver avuto l’idea di associare l’uovo alla Pasqua. Proprio qui, infatti, l’uovo veniva bollito poi decorato con dei fiori e donato come regalo Pasquale. Le simbologie dell’uovo con elementi rappresentativi forti non associati alla Pasqua hanno comunque origini antichissime: Nella Mesopotamia l’uovo era simbolo della vita.

Per i Pagani l’uovo rappresentava un simbolo di fertilità e proseguo della genesi. Gli antichi Romani usavano dire: “Omne vivum ex ovo” – Tutto il vivere viene dall’uovo. Quindi la circolarità e la perfezione dell’uovo era associata alla nascita del tutto. Proprio dagli antichi romani, partirà la pratica di decorare e dipingere le uova come buon augurio di nascita.

Gli Egizi e gli Indiani credevano che l’universo si fosse formato da un grande uovo e che le due estremità di esso fossero il cielo-la terra, inoltre, l’uovo era associato a riti di fertilità Anche per i Cinesi, l’uovo rappresentava la perfezione dell’unione tra “Yin-Yang” – “la terra-il cielo”. Per i Persiani e Greci, ancora oggi, l’uovo rappresenta il simbolo di una nuova primavera e viene regalato proprio come augurio di un nuovo anno.

In Israele l’uovo è un simbolo di buon augurio e si usa donarlo agli amici o anche regalarlo per il compleanno.

Una legenda Cristina parla del miracolo delle uova rosse. Pare infatti che Maria Maddalena di ritorno dal Santo Sepolcro prima di annunciare il miracolo della resurrezione di Cristo ai discepoli si sia imbattuta sulla strada con Pietro, il quale non credette alla notizia di Maria Maddalena e le disse; “Ti crederò solo se le uova che porti nel tuo cesto si coloreranno di rosso” e così avvenne. Da qui l’uovo divenne il simbolo della resurrezione di Cristo dalla sua tomba alla vita eterna. La Pasqua celebrata dai primi Cristiani consisteva nel regalare le uova avvolte in foglie i nobili usavano le foglie pitturate d’oro.

Oggi il giorno di Pasqua si usa giocare con le uova colorate. In Abruzzo si gioca “ lu’ scucchia latt” che prevede che ogni partecipante abbia l’uovo sodo che picchietta insieme ad un’altra persona anch’essa con l’uovo sodo in mano vince la gara chi arriverà alla fine del gioco con l’uovo intatto. In Francia, Germania e Austria, “egg picking” è il gioco più amato, le persone tengono in mano un uovo sodo che lasciano rotolare nello stesso momento da una collinetta, l’uovo che arriverà alla fine con meno spaccature vincerà. In Lussemburgo, invece, si dona ad ogni bambino un cucchiaio su del quale viene riposto l’uovo sodo, il bambino che porterà l’uovo alla fine del percorso senza farlo cadere vincerà.

Da questo excursus storico possiamo concludere che l’uovo, con la sua perfezione sferica, e portatrice della vita, in qualsiasi paese e in qualsiasi periodo storico racchiude i simboli: di rinascita, di nascita, è un augurio di vita, di pace e serenità. Vi auguro una buona Pasqua che possa essere la migliore di sempre.

Easter Tradition / Pasqua Tradizione

Easter time 1960, I was 17-years-old and my brother Al and I were on spring break from school working at my dad’s gas station at E. 19th and Carnegie Ave. This was always a welcome springtime break.

The Saturday before Easter was always festive and active since all our regular customers wanted their cars hand-washed and sparkling clean. Our customers came from all walks of life; rich, poor and of all faiths and statuses. Lent had passed and special treats were everywhere. Our station was an intense hustle and bustle on all cylinders.{mprestriction ids="*"}

On that late Saturday afternoon, brother Al and I realized we forgot to go to dad’s cugino florist to get mom an orchid corsage. We remembered a little shop near Central Market – now the Progressive and Quickens Loan area – and motored there to find out what might be left. We entered and a tiny Italian man, no more than 5-feet-tall, asked what we needed. We told him but easy pickins’ was out of the question. He picked up on our facial disappointment.

He walked to the cooler and returned with a picture-perfect orchid. He winked because the store was moments away from closing and gave us a 50 percent discount. We couldn’t believe our good fortune and jumped at the deal. We wished him Buona Pasqua and, on our way out, noticed a next-door bakery with lamb cakes. Though they didn’t measure up to mom’s, we bought one.

That Saturday trip to the tiny shop at the Central Market became standard operating procedure until 1964. Mom passed away in December of that year. However, late in the day on the Saturday before Easter 1965, we went to that floral shop and that same little Italian had one orchid corsage left. He told us this was the “grand finale.” He was retiring and closing shop. This time he refused to take any money for that final orchid corsage. It was a tearful event. When we left we also noticed no lamb cakes in the next-door bakery as that business had been retired as well. There would be none at our Easter table. Mom was gone but certainly not forgotten. The next day we brought that beautiful corsage to her at the cemetery.

We’ve learned that the book of life closes on everything and, sadly, includes all the good things. But, change is like night following day; destined for everyone and needs to be expected. Buona Pasqua!{mprestriction}

Paying homage to the bones of St. Valentine

Celebrating St. Valentine’s Day in Italy isn’t difficult. The whole country is romantic, from a gondola trip in Venice at Carnival time, to the colours and perfumes of early blossoms in Sicily with a snow-clad Etna simmering in the background. But these are clichés. I propose a rather more original take for an Italian St. Valentine’s Day outing.

The little town of Monselice in the Veneto clusters itself around a volcanic cone, a little separated from the others in the Euganean Hills. On top, of course, is a ruined castle, but there’s a better-preserved one a little way up the hill. I like this castle. It’s not so crumbling that it would be impossible to live there. It has a romantic “Juliet” balcony where the custodian is wont to give impromptu recitations of Shakespeare in Italian, and the music room has stuccoed walls painted in a checkerboard of cream and terracotta. But this romantic location isn’t what I have in mind.

Wander from the cobbled courtyard of the castle up the viale delle sette chiese. This lovely little lane is guarded by two lions on top of pillars looking at each other, one rather sadly, and one, wearing on his head a cross between a crown and a Venetian chimneypot, grimacing and baring its teeth, perhaps because he’s lost a paw.

The seven chapels each contain a large, but not very good oil painting, and are painted a brilliant white and yellow, spaced at regular intervals leading to the Villa Duodo. This villa has its own, more special, chapel, cared for by an over-friendly gentleman who rather likes to fondle female tourists, of whom there are not very many. He tries to entice them into the sacristy to buy the sort of tacky souvenirs you might win at a fairground “for the upkeep of the chapel.”

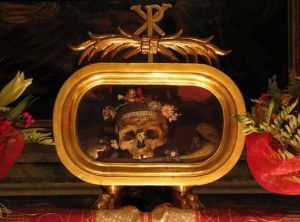

Better to avoid the sacristy altogether and walk straight through to the main altar where a strange sight awaits. Arranged on shelves in a semi-circle are dozens of diminutive skeletons dressed in 17th and 18th century costumes, apart from their exposed skulls.

They’re all labelled in beautiful, faded copperplate lettering, with prominence given to the central little skeleton, clad in red velvet and identified as St. Valentine. His presence is used as an excuse for a great festa in Monselice on February 14th. The whole little town is given over to processions and feasting, the focus of which seems to be giant mortadellas, like tree trunks, lying in the streets waiting to be sliced.

St. Valentine, I have discovered, was active as a priest in the 3rd century AD when young men were banned from marrying because it was felt that they made better soldiers if they were single. Valentine defied this decree and went on marrying young couples. When he was thrown into jail and tortured, he fell in love, it’s said, with the jailer’s daughter. Before his execution, he sent her a note “from your Valentine” and that’s how it all began.

When I first saw the macabre display of small skeletons in Monselice I wanted to know whether they were all the remains of children. Reluctant as I was to make contact with the donnaiolo custodian with a penchant for the ladies, I went into the sacristy to ask that very question. His answer was curious and illuminating.

He explained how the skeletons were all bought by the owner of the grand villa at the time of the clearing of the catacombs in Rome. Aristocrats readily assumed that these were the bones of Christian martyrs, and could be venerated as saints. Buying a job lot for decent burial could guarantee them their entry to Paradise. Our particular local grandee had decided to build only a small chapel, but had acquired rather a lot of skeletons. His solution was simply to use the upper bodies, the feet and the skulls, and throw the leg bones away, making them much shorter, with space for more saintly occupants along the shelves.

“But what about St. Valentine?” I asked, rather disappointed.

“Well, signora,” he replied, tapping the side of his nose with his finger. “Perhaps it is, and perhaps it isn’t, but we in Monselice believe that St. Valentine rests here, and we certainly enjoy celebrating his feast day every 14th of February.”

The Legend of St. Valentine

Legend has it that the Valentine takes its name from a young Christian priest who lived during ancient Roman times. During that period, Christians were jailed because of their faith and so it was with Valentine.

Often he thought of his loved ones and wanted to assure them of his well-being and his love for them. Within reach, beyond his cell window, grew a cluster of violets. He picked some of the heart-shaped leaves and etched ever so delicately, "Remember Your Valentine" and sent them off by a friendly dove. As the days passed, he sent more messages that simply said, "I love you." Thus the Valentine had its beginning.

By order of Claudius the Goth, St. Valentine was beheaded for his faith on February 14, 269 in Rome, Italy.

Because of the love this young priest had for his Lord and his people, his name has become beautifully and indelibly associated with the love that people have for each other.

Whatever the origins of this ancient tradition, two things are evident. Valentines are sent as an outpouring of love, affection and devotion and received as one of the most beautiful gestures and nicest compliments one can present to another.

Easter Traditions

While you probably won't see the Easter bunny if you are traveling to Italy this Easter, you will have the opportunity to experience many wonderful Pasqua traditions. The days prior to Easter host solemn processions and masses while Easter day is a joyous celebration. The Monday following Easter, la Pasquetta, is also an Italian holiday.

Many towns host religious processions on the Friday and Saturday before Easter. Solemn in nature, these processions have special statues of Jesus and the Virgin that are paraded through the city. Parade participants are often dressed in traditional ancient costumes. On Good Friday, in Enna, Sicily, more than 2,000 friars dress in ancient costumes and walk through the streets. The Good Friday procession, Misteri di Trapani, in Trapani, Sicily is 24 hours long.

Rome is the top Italian destination for Easter week as the most popular Easter mass is held by the Pope at St. Peter's Basilica. Mass typically starts at 10:15 A.M. and the Pope gives the Easter message and blessing at noon in the central loggia of St. Peter's Basilica. On Good Friday, the Pope gives mass at 5 P.M. and, immediately following, begins his walk to remember Christ's Via Crucis, Stations of the Cross, making 14 stops along the way. He ends at the Colosseum to give his blessing.

One of the oldest Easter traditions in Italy is La Festa del Carro in Florence. During the Crusades, Pazzino di Ranieri de' Pazzi, a Florentine knight, raised the Holy Cross banner in Jerusalem and received pieces of flint from the Holy Sepulcher of Christ for his bravery. Upon his return to Florence, these stones were used to light the Easter Vigil sacred fire. Today, Florentines commemorate this event with a procession on Easter Sunday in which a 30-foot tall antique cart is pulled by white oxen through their city. Once the cart reaches Santa Maria Del Fiore in Piazza del Duomo, a dove-shaped rocket holding an olive branch is shot towards a cart loaded with fireworks, setting off the scoppio (boom). This event is meant to bring a bountiful harvest, stable civic life and growing business.

Obviously food plays a big part in the Easter holiday. Traditional Easter foods include lamb, artichokes, and special Easter breads: Pannetone and the dove-shaped Colomba. And for dessert? Large, hollow chocolate eggs that typically come with a surprise inside are popular Easter treats.

The Monday after Easter, Pasquetta, is a jovial celebration. According to tradition, people are free to celebrate as they wish. It is common to have a picnic or barbeque and many natives head to the countryside or the seaside. Easter Monday is a time to gather with friends and have fun.

Easter in Italy is a perfect time to celebrate long-standing traditions. Visiting during this time of year will no doubt yield a wonderfully unique experience.

The Sweet Carnival in Venice

Never before in this period does the proverb "Semel in anno Licet insane" (once a year you are allowed to go crazy) seem to fit the reality of what happens when a whole city falls into celebration; not only with its masks and wonderful costumes, but also with the arrays of sweet treats displayed by all the local bakers and cake shops. It is a sheer delight for all gourmets and also for those who would tend to avoid excess calories. During the Carnival, it is virtually impossible to resist all of the sweet temptations which abound in all corners of the city, in the form of galani (sweet, deep-fried, thin, short crust pastry strips) or frittelle, the authentic Venetian puffed, sweet dumpling stuffed with sultanas, with patisserie cream or zabaglione, sprinkled with an intangible, but dazzling sugar icing, sometimes slightly scented with vanilla.

But, as with any self-respecting party, during the Venice Carnival, the Queen of cakes is the Frittella. The oldest recipe is given by Bartolomeo Scappi, who used to be the private chef of Pius V. The Venetian Historian Giovanni Marangoni writes that in the '700 the frittella became the "national cake of the Venetian State." In Venice, the fritole were considered the national dessert, right back from the days of the Serenissima Republic, and you could taste them not only in Venice, but throughout the Veneto region of Friuli, up to almost the outskirts of Milan.

The fritole, the undisputed queen of Venetian sweets, was produced in the various streets of the city, as well as in homes and bakeries, but mostly in wooden square-shaped huts.

The fritole were prepared by the "fritoleri, who were both producers and sellers. In the '600, the fritoleri, to emphasize their exclusivity to this delicacy, formed an association composed of seventy fritoleri, each with its own area where they could exercise this particular business and each one of them could pass on the licence exclusively to his children. The corporation remained active until the fall of the Republic, though the art of fritoleri definitively disappeared from the streets of Venice only in the late 19th century.

"They always have a sort of a diaper in the front which resembles a woman's apron and which appears to have just come out from the laundry. They hold in their hands a jar with holes with which they throw sugar on the goods, but which at the same time seems to say: who can smell and taste what we are sugaring?" This is the way they were described by their contemporaries. In the early 19th century, the recipe was described in verses indicating the rules which have remained famous, "They must be very tasty; well cooked and well raised. A little sugared, cold or hot, as you please."

Even if the only real frittella remains the Venetian one (stuffed with raisin and candied peel), all over Veneto different local recipes have spread. Nowadays you can find those dipped in batter made with fruit, flowers or vegetables; in some cases with weeds and grass of the mountain, and even with rice and polenta. But, the influence of fritoe spread to other cultures, so that there is even a Jewish frittola which the Venetian Jews still prepare for the Feast of Purim.

To taste these typical Venetian cakes is a must for Carnival, perhaps if you accompany it with a good hot coffee or hot chocolate to warm up the cold nights of February, or with a fresh, sparkling Prosecco, a Venetian wine ideal as an aperitif or with dessert.

This is one of our recipes, the real Venetian Frittella!

FRITOE AEA VENESSIANA - VENETIAN FRIED SWEET DUMPLINGS

Ingredients

500 g. Plain flour

20 g. Fresh yeast (dissolved in a little warm water)

80 g. Sugar

2 eggs

Milk

Zest of 1 lemon

80 g. Raisins (immersed for 1 hour in a bit of grappler or Rhum)

Oil to fry

Icing sugar

Salt

Directions

Dissolve the yeast in a little warm water with the sugar. Add this to the flour, along with the eggs, lemon zest and a pinch of salt. Start mixing and slowly add a little milk at a time, until the dough is smooth and soft. Keep mixing until you see bubbles appearing. Cover the bowl with a wet towel and leave to rest for 2 hours in a warm place.

After 2 hours, add the raisins (not the juice they released) to the dough. Make some little balls and fry them in a deep pan with hot oil (if the dough is too soft and you cannot make the balls, use a small spoon to pour the dough in the hot oil). Take the little fried balls out of the hot oil as soon as they are a nice golden colour. Don't fry too many balls at the same time, they will burn on the outside and will not cook on the inside.

Drain the balls on some kitchen paper, serve them warm, covered by icing sugar. Best eaten the same day and with a nice glass of prosecutor wine.

Christmas Traditions

- Christmas and the Christmas carol originated in Italy

- Devoted to Jesus, Saint Francis wrote a Christmas hymn in Latin, "Psalmus in Nativitate," but, apparently, no Christmas carols in Italian.

- Franciscan friars are credited with several 13th century Italian carols.

- The earliest known permanent nativity was created for the Rome Jubilee in 1300.

- One of the largest nativity scenes is displayed at Saints Cosma and Damiano above the Forum in Rome. The Naples-style presepe of royalty dressed in fine fabrics was commissioned by Charles III of Naples and later purchased by the city of Rome and restored in the 1930s.

- From the massive fortress of Castel of Sant'Angelo in Rome, a cannon is fired to proclaim the opening of the Holy Season. Emperor Hadrian's mausoleum takes its name from the vision of the angel by Pope Gregory the Great in the 6th century.

- The Ceppo (Yule log) is burned and wine toasts and wishes for the future are proclaimed.

- The Baroque Piazza Navona is the flamboyant social center of Rome and a site for unique Christmas gifts and luxurious shops. Venetians pride themselves in their Campo Santo Stefano market filled with stalls selling handicrafts, nativity scenes and figurines, toys and seasonal treats. Food, drink and music complement the festivities.

- The Santo Bambino statue carved from olive wood from the Garden of Gethsemane was ship-bound for Rome but sank. The statue miraculously washed up on shore and was eventually blessed by the pope and kept in the 6th century Church of Santa Maria Aracoeli. It was stolen in 1994 and is still missing. A reproduction has been made from carved olive wood. Roman children write their Christmas letters to Santo Bambino.

- Christmas trees are not an Italian tradition, but are becoming increasingly popular. Though there is one in Rome's Saint Peter's Square, the two largest are in Piazza Venezia and next to the Coliseum.

- A strict fast is observed 24 hours before Christmas, after which a meal of varying meatless dishes is served. Traditionally, there's an assortment of fish, calamari, pasta, vegetables, salad, fennel, fruits, chestnuts and sweets.

- An old tradition is the Urn of Fate. This large bowl holds gifts for family members. Each member takes a turn at drawing a gift until the bowl is empty.

Happy Easter. Now Let's Roll Some Cheese!

Easter (Pasqua) is a holiday with universal significance throughout Christianity, but is celebrated in very different manners across the world. In Italy, Easter is a weeklong holiday that finds most children off from school and many adults taking off work from the Wednesday before Easter until the Wednesday after Easter. There is an air of somberness in the days leading up to Easter, which consist of processions of people in traditional costumes carrying large statues of the Virgin Mary and Jesus, as well as masses, displays in public squares and even reenactments of the stations of the cross.

Easter Sunday, however, is a day of joy and celebration with endless food and wine, often celebrated with friends and neighbors. In fact, there is a popular saying among Italians, "Natale con i tuoi, Pascua con chi vuoi," which loosely translates to "Christmas with family, Easter with whomever you choose." The celebration continues into the Monday following Easter, known as la Pasquetta. La Pasquetta is a national holiday in Italy, one that usually celebrates the beginning of the warm weather where people pack picnics made from their Easter leftovers and take them to the openings of their local parks.

Festivals and celebrations take place throughout Italy on la Pasquetta, with one of the oldest, most famous and, well, most bizarre events taking place in Panicale, a village set in the hills of Umbria, completely surrounded by a stone wall and dating back to medieval times. On la Pasquetta, the locals in Panicale gather for the annual Ruzzolone, or "rolling the cheese," a competition said to be over 3000 years old, having originated during the Etruscan times.

Ruzzolone is a competition with elements of bocce, bowling and even yo-yo. The giocattori, or players, attach a large, leather strap with a wooden handle around a nine-pound wheel of pecorino cheese and use that strap to launch the cheese wheel through a course of curvy streets that wrap around the village walls. After each launch, the crowd runs alongside the wildly rolling cheese wheel, and when it comes to a stop, that place is marked with a piece of chalk. Since the cheese is not always the easiest thing to control, it often rolls off-course into the hillside with officials chasing after it. In this case, they take the chalk, and mark the spot where the cheese left the course.

The goal of Ruzzolone is to move the cheese wheel throughout the course with the least amount of "strokes." Of course, it is a success just to get the cheese wheel to remain intact by the end of the course. The winner of the competition gets to bring home the wheel of cheese, and if any cheese breaks along the way, everyone gets some of it!

The funniest part of Ruzzolone is that most people don't even stick around to see who wins it. By the time the course is completed, most of the spectators have been drawn to the village square for a festival of music, free hard-boiled eggs and, of course, free wine! Buona Pasquetta a tutti! (Happy Pasquetta to all!)

Photo courtesy of www.italiannotebook.com

The Christmas Season in Italy

From the Feast of St. Nicholas on December 6 to Epiphany on January 6, Italians have found many ways to honor the birth of Christ beyond the calendar day of December 25. Activities based on the importance of saints, customs, and traditions vary among different villages, cities and regions. In joyful anticipation of Christ's coming and commemoration of his birth, specialty foods, music, processions and bonfires are at the heart of most of these celebrations.

The Feast of St. Nicholas on December 6 celebrates the momentous arrival of the saint's remains in Italy in the 11th Century. Though St. Nicholas was of Greek descent, born in Asia Minor and made Bishop in Myra during the 4th Century, his partial remains were secretly moved to Bari, Italy by Italian sailors in 1087. Christians feared that when the Turks invaded Asia Minor, they would be unable to make pilgrimages to Myra to honor the saint at his tomb, and so the sailors took off with the human relics so that he could be honored elsewhere.

Nicholas' history was one of endurance through the Christian persecutions. His dedication to Christianity, his love and generosity offered for those in need, and the multiple miracles attributed to St. Nicholas made him a widely venerated figure. He is a patron saint of many children, maidens wishing to be married, scholars, mariners, and prisoners-just to name a few.

The Basilica di San Nicola was built in honor of St. Nicholas in Bari. Each May, the statue of St. Nicholas, or Nicola, is taken out to sea for the day. While the statue is at sea, throngs of people, including dignitaries of the town, gather to welcome the statue back to Bari. A candlelight procession helps to lead the statue back to the basilica.

On the eve of December 6, cities such as Molfetta and Trieste await the coming of San Nicola as other cultures would wait for Santa Claus. Children leave letters for him asking for gifts and promising good behavior for the following year! While the children are sleeping, San Nicola leaves chocolates, candies and other special things. Family patriarchs dress up as St. Nicholas and hand out gifts. Coal is given to children who have misbehaved.

The Feast of St. Lucy, or Santa Lucia, comes next in the holiday season on December 13. Lucy was a young girl from Siracusa, Sicily who tragically suffered at the hands of pagans for her devotion to Christ. Specifically, the man to whom her mother committed her for marriage was so embittered by her refusal of marriage, that he turned her in to authorities. Dragged by oxen, eyes torn out in an attempt to get her to refute her Christianity, no amount of torture could get Lucy to give in. History recounts that around the year 310, a fire was set to torture her but the fires just wouldn't stay lit. She was then stabbed in the throat with a dagger but appeared to only die once she was given the Christian sacrament. She is known as the patron saint of those with eye problems.

St. Lucy's remains can be venerated at the Church of San Geremia in Venice. Her head was sent to Louis XII of France and still remains there in the Cathedral of Bourges.

To mark the Feast Day, torchlight processions and bonfires commemorate the young girl whose name means "light." This also goes along with the winter solstice which occurs around the same time.

The meal most commonly associated with the feast day is Cuccia, a cooked wheat porridge that can be made savory or sweet. As the story goes, during a famine in Sicily, the people invoked St. Lucy and were rewarded with a ship appearing in the harbor filled with grain. A sweet version of Cuccia is a mixture of cooked wheat, fig honey, orange peel and walnuts. Some Sicilians refuse to eat wheat on December 13 to honor St. Lucy. Almond cookies, made to resemble eyes and served in pairs, are often served during the Feast of Santa Lucia so that people recall the torture she had to endure.

In certain regions of Northern Italy, St. Lucy is the gift-bearer during the Christmas season, and as with other occasions, coal was left for naughty children! According to tradition, Lucy travels around on a donkey to deliver the gifts. Children leave coffee for Lucia and a bowl of milk and carrots for the donkey.

In regions such as Lombardy and Veneto, Goose is the main fare for the holiday. In Udine, Venice, where her bones are buried and many go to pray to Lucy, frico, or fried cheese wedges are served to honor her memory. Children receive candy and gifts and sing for the Feast.

In preparation for Christmas, many Italians pray Christmas Novenas-nine consecutive days of prayer which ends at Midnight Mass on Christmas Eve. In Rome and some other Italian cities, the sounds of bagpipes can be heard ringing through the streets to announce that Christmas is near.

The Nativity, above all else, is the centerpiece of decorations. The image of the Holy Family as seen in the crèche (as legend tells us was first created by Francis of Assisi) symbolizes the two most important parts of Christmas for Italians: the birth of Christ and family togetherness. From living Nativities traveling from home to home or stationed in the Piazzas, to the still figurines, whether small or life-size, these scenes adorn every imaginable public place and private home.

Christmas Eve traditionally begins with a sumptuous meal, meatless, and usually comprised of multiple fish dishes-seven fishes is the number most commonly associated with this meal. Capitone, or fried eel is a favorite main course. (On a personal note, I will never forget the Christmas Eve that my Aunt Sylvia, never averse to making jaws drop, had a giant eel sitting on the table as her centerpiece of food. We American-born children just squealed and ran for the other room!)

Following Christmas Eve dinner, many attend Midnight Mass. The Pope presides over the Mass at the Vatican-a most solemn and moving event. Some families stay up the whole night following Mass enjoying games and celebrating!

Christmas Day is simply spent enjoying family time. Christmas dinner is served midday. Meat-filled ravioli or tortellini is one of the most traditional Christmas meals. Lamb and gooseliver are often included in the menu, served with accompanying vegetables and mashed potatoes and lentils.

Sweet breads such as Pannetone (from Milan), Pandoro (star-shaped from Verona), Pangiallo (Roman), Panforte (a dense fruitcake from Sienna dating back to a 13th Century monastery), Panpepato (a gingerbread cake from Ferrara and Tuscany), and Pandolce (Genovese) are served for dessert.

Almonds, served in a number of desserts such as torrone and other cookies, are very traditional and important to include in a Christmas meal because, according to folklore, eating nuts contributes to the fertility of the earth and its people.

Celebrations continue for New Year's Eve and New Year's Day for Italians. Being in the company of good friends is very important for New Year's Eve. It is also customary on New Year's Eve to discard unwanted items from the house-from clothing to furniture. New Year's Day is the time to claim others' discarded items. One might even find a Fendi bag among the giveaways!

Typically, the menus served on Christmas Day are served again on New Year's Day.

Epiphany, also known as the Feast of the Three Kings, is celebrated on January 6 and is the highlight and the conclusion of the Christmas Season for many in Italy. On the eve of Epiphany, Italian children prepare for the arrival of La Befana, a somewhat dilapidated, but lovable witch who rides her broom around bringing gifts to good children. Stockings are hung by the chimneys, much like in the tradition of Santa Claus.

According to legend, a few days before the birth of Jesus, Befana was asked to join the Magi to follow the star to find the Christ Child but declined, stating she was too busy with her chores. After the Wise Men left, Befana realized she should have gone with them and tried to follow them with a basket full of sweets. She never found the Three Kings or the Baby Jesus, and it is said that on each Epiphany she flies around on her broomstick still trying to find them.

No matter which tradition is celebrated, the most essential parts of the holidays for the Italians still remain: faith, family and food.

Italian Christmas Traditions

For Italians, December 25th is without any doubt the most important day on the calendar. Christmas, a day that has mainly a religious meaning, began in Italy around 300 A.D., when Emperor Constantine, after adopting the new faith of Christianity, celebrated the birth of Christ for the first time in history. The feast day of the Romans' old pagan god, Mithras, fell on December 25th and that was the day chosen to honor Christ.

The tradition of the Christmas tree began many centuries later, and was introduced in Italy by populations from other countries. Today in Italy, though you can see many Christmas trees, the traditional symbol among Italian Christmas decorations remains the Nativity scene. Built in various sizes with different materials, mangers or presepe, are very common in Italian houses, particularly in the South. The Neapolitan presepe are very famous and most of them are works of art, built of papier-mâché, wood or cork by experienced artisans, who have passed on their skills from generation to generation, like those found on Via San Gregorio Armeno. According to the tradition, at midnight of Christmas Eve the youngest of the family places Baby Jesus in the manger to symbolize his birth. In some small towns there is a live Nativity scene, like the one in Caltagirone (Sicily) with adults and kids impersonating the various characters.

The holiday period, which goes from Christmas Eve to the Epiphany, is dedicated to the family. An old saying goes "Christmas with your family and Easter with anyone you wish." The most characteristic Italian Christmas sound is the one of bagpipes, played by pipers called zampognari. They are shepherds who live in the mountains and go down to the plains at Christmas time to play on the city streets. The melodies they play are adaptations of old traditional, country tunes. Modern "zampognari" still dress like their ancestors did, with sheepskin vests, leather breeches, a woolen coat on their shoulders, and knee-high leather strapped shoes bind their white stockings.

Yet we cannot talk about Italian Christmas traditions without talking about food. On Christmas Eve Italians used to eat the classic "cenone" (literally "big supper"), made up of several courses. Especially in the South, traditional food for this evening are broccoli with garlic, oil and lemon, spaghetti with clams, fried salted cod, big fried eels, boiled cauliflower with olives, anchovies and capers. The big supper ends with fresh and dried fruit: walnuts, peanuts, chestnuts, almonds, roasted pumpkin seeds, figs and torrone. Among the Christmas desserts there are panforte in the North and struffoli in the South. Panforte is a typical dessert from Siena, round and flattened, made from flower, almonds, sugar, candied fruit and cooked in the oven. Struffoli, of Greek origin, comes from a mixture of flower, eggs, sugar and butter. The dough is then cut up into little balls and fried in boiling oil. The little, fried blond balls are dipped in honey and sometimes mixed with candied fruit and. Naturally, a slice of panettone (brioche cake with raisins and candied fruit) or pandoro (without raisins) is never rejected. Finally the whole family enjoys playing tombola (bingo) until late at night.

In Italy the year ends with the celebration of New Years Eve (the feast day of Saint Sylvester) when colorful fireworks light the sky as the clock strikes midnight. In some old city neighborhoods people still observe the tradition of throwing broken household items out the window. So you might see broken chairs, bags of old clothes or anything they no longer use, flying from the windows above and onto the street below.

Holidays for the Italians go on after New Years Day. Although most presents are exchanged on Christmas Day, the Epiphany on January 6th means some more gifts for children. According to the Catholic religion, on this day the three Kings arrived in Bethlehem to offer their gifts (gold, incense and myrrh) to Christ. As tradition goes, an old woman called Befana, riding her broom, brings stockings full of candies and gifts to all kids who have been well behaved during the previous year.

The Christmas holidays end with the Epiphany. Children go back to school and adults go back to work. As an old saying goes: "Here is the Epiphany Day that carries the holidays away." Merry Christmas and Happy New Year to everybody!