Some historians have called the 1950s the greatest period of peace and prosperity in America. The decade represented a golden era of achievement, undergirded by an affirming age of simplicity when homespun, working values and patriotism were at an all-time high for the multitudes of the multicultural, multiethnic makeup of its citizenry.

America was a “melting pot” and new economic opportunities were spurred everywhere in industry and education. Nationalism and optimism permeated all segments of society and most felt the positive effects that were sweeping the national landscape, clamoring chants of America’s superiority and greatness in the world.

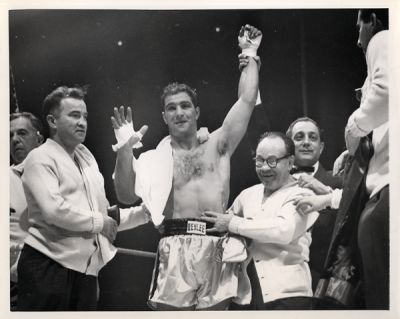

During WWII and immediately thereafter, Americans came to appreciate their sports heroes like heavyweight boxing champion Joe Louis and Yankee greats Joe DiMaggio and Yogi Berra; all served honorably in the war effort and returned home to garner championships, fame and enduring respect. Enter Rocky Marciano, in the early 1950s, the “Brockton (MA) blockbuster,” also returning from honorably serving in WWII. He defeated former heavyweight champions Joe Louis and Jersey Joe Walcott in knockout fashion to claim the undisputed, heavyweight boxing championship, shocking most in the civilized world.

How could a first-generation, Italian American and the son of a non-union, native Italian shoemaker suddenly rise to become the heavyweight boxing champion of the world? Marciano had achieved the American dream and almost everyone appreciated him; some even loved him.

Marciano, originally named Rocco Francis Marchegiano at birth on September 1, 1923, achieved the unthinkable and unimaginable to become the boxing world champion. “Get out of this factory and be somebody important,” Marciano’s father, Pierino, a native of Abruzzo, would repeatedly urge and remind his oldest son, Rocco, fueling him emotionally to do something “special” and rid himself of oppressive factory work and imminent poverty. Young Marciano feared poverty most for his parents and he wasn’t going to let that happen, remembers his younger brother, Louis.

Marciano felt pressured to make something special of himself and rescue his family. As the eldest son, he was compelled to remove his family from an impoverished and limited lifestyle in their modest section of an old and immigrant-filled city of Brockton. He had a burning desire to succeed and make his Italian parents proud; “family first,” the most important Italian mantra, was honorably accepted by the oldest, first-generation son.

Marciano realized as an adolescent that academic achievement came with difficulty and he dropped out in the 10th grade, working with his father in a shoe factory and driving a coal truck in Brockton. This was not the end game he wanted for himself or his parents. Marciano was stronger than most adolescents and developed a reputation as a “tough Italian kid.” He worked hard at baseball and was an outstanding hitter for a catcher, turning heads as he drove baseballs out of the James Edgar Park near his house. His hitting display afforded him an eventual tryout with the Chicago Cubs. He did well, but was cut because he lacked right arm strength in his throws to second base as a catcher.

Marciano was humbled but not discouraged and shifted his training to become a heavyweight boxer despite being harshly forbidden not to do so by his mother, Pasqualina, a domineering and protective, robust mother. “Rocco, figlio mio, cuore di mama.” “Rocky, my son, and the heart of my life,” she would proudly say to family and friends. Most believed that Marciano’s strength and tenacity was from Pasqualina’s side, the Napolitano half of Marciano’s lineage.

To mask his training efforts, Marciano and his best friend and training partner, Allie Columbo, would run the streets of Brockton tossing a football back-and-forth to prepare him for a tryout in professional football, as they told Pasqualina. At first, they had her fooled.

Columbo strictly monitored Marciano’s diet as well, regulating him from overeating his favorite Italian pasta dishes prepared in earnest by Pasqualina. Columbo would later marry Marciano’s younger sister, Elizabeth, in 1955.

Marciano was on a “no-lose” mission to achieving greatness and he did so by simply out-working and out-conditioning all fighting foes. For starters, he ran seven miles a day through the streets of Brockton with Colombo, sometimes eating fresh fruit tossed to him from the native Italian grocers, cheering him on in Italian for his next fight – a fight that he always won.

Marciano’s work ethic was nothing short of remarkably consistent and disciplined: hours of gym work, sparring, hundreds of push-ups and sit-ups, countless medicine-ball thumps to the gut. Marciano was committed to his training regimen.

His boxing career was almost golden, achieving a 49-0 record with 43 knock-outs and retiring as the only undefeated, heavyweight boxing champion in history. Perplexingly, most boxing historians have him ranked no higher than eighth all-time, citing weak heavyweight competition in his era and his undersized physical stature at 5’11” and 187 lbs.

Marciano characteristically beat his competition by hitting them more often than other fighters and by relentlessly chasing them around the ring until his opponents got weary. Typically his opponents would, then, unconsciously drop their hands and get tagged to the jaw with Marciano’s heavy hammers from the floor. He dropped foes like old timber with his powerful right hand, famously known as his “Suzie Q.”

He is remembered and honored for his class as an individual and being a winner in everybody’s book. Ask the Brockton residents for evidence. They always bet on Marciano and they never lost. Some even paid off mortgages with Marciano winnings, as Brockton sports lore records. Rocky Marciano is deservingly recognized as Brockton’s all-time favorite son.

https://www.lagazzettaitaliana.com/people/9303-italian-great-rocky-marciano-lived-the-american-dream#sigProId525f76b7f3