Lo sciopero dei minatori di carbone del 1873 voleva essere una ferma protesta contro i tagli dei già bassi salari nella valle di Mahoning. Sfortunatamente, sebbene si protrasse per otto mesi, non raggiunse mai l’obiettivo desiderato. La pratica, infatti, da parte dei ricchi proprietari delle miniere di assumere immigrati dall’Europa (tra cui moltissimi italiani in cerca di un qualsiasi impiego) al fine di sostituire gli scioperanti, costrinse i minatori organizzati a tornare a lavorare ai salari prevalenti pur di non perdere del tutto il proprio posto. Durante lo sciopero e anche in seguito si verificarono episodi di violenza causati da scontri e tensioni crescenti tra gli scioperanti ed i loro sostituti, che furono poi licenziati una volta che le agitazioni ebbero fine. Questa costituì la prima “ondata” documentata di arrivi di italiani del Meridione nella valle di Mahoning. Dopo la conclusione dello sciopero, molti si stabilirono nella Piccola Italia di Coalburg.

In the Mahoning Valley, there’s a layer of fine coal dust that overlays Italian American history. To retrace the time when Italians first arrived, head north on Youngstown’s Belmont Avenue and you’ll soon find yourself on Route 193. In Liberty Township, not far from where the highway crosses Churchill Road, stood Church Hill and its coal camp. The events that took place there, forgotten for decades, deserve a retelling.

In the Mahoning Valley, there’s a layer of fine coal dust that overlays Italian American history. To retrace the time when Italians first arrived, head north on Youngstown’s Belmont Avenue and you’ll soon find yourself on Route 193. In Liberty Township, not far from where the highway crosses Churchill Road, stood Church Hill and its coal camp. The events that took place there, forgotten for decades, deserve a retelling.

The Mahoning Valley was once home of rich, bituminous coal deposits that yielded a black mineral in no need of refining. Often referred to as Sharon Block No. 2, it fueled iron foundries in the vicinity and those as far away as Cleveland and Chicago. This local, high-grade coal spurred development and created the first millionaires in the Valley.

The Unification of Italy produced a new country, the Kingdom of Italy. The fledging government’s policies of raising taxes and converting communal and church lands into real estate hit the peasant population particularly hard. To add to the troubles, a bandits’ war against the Kingdom threw the Southern countryside into chaos. The result caused thousands of Italians to leave for Northern Europe and the Americas. Previous Italian immigration to the U.S. had been negligible, but by 1870, immigrants arriving on the East Coast reached the thousands for the first time.

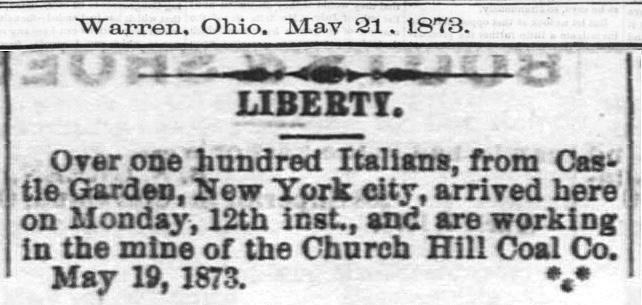

Back in the United States, miners in the Mahoning Valley declared a strike in response to the operators’ decision to reduce wages by 20 percent. The Church Hill miners were the first who refused to accept the cut; they walked off the job on New Year’s Day, 1873. A month later, the work stoppage remained solid with little sign of weakening. Anxious to gain the upper hand, coal operators recruited destitute Italian immigrants from New York City to break the miners’ walkout.

Unlike subsequent generations of Italian immigrants, these first arrivals had no contacts or job offers in the United States. The penniless immigrants ended up at government expense in a large shelter on Ward’s Island, on the grounds of an insane asylum. Shipload after shipload of economic refugees from Italy continued to arrive, overcrowding the holding facility. When the coal operators from the Mahoning Valley sent recruiters to tap this idle labor force, 200 Italians responded to their call between March and May of 1873. One group arrived in Coalburg, Hubbard Township, and the second, a few months later, in Church Hill, Liberty Township.

The settled population of mostly British and Welsh miners reacted violently to the newcomers whom they saw as foreigners threatening their jobs and way of life. Coal operators evicted strikers while giving lodgings to the Italians. In Church Hill, families of strikers lost their homes during a raging March blizzard. Soon after, miners torched properties belonging to the Church Hill Coal Company. Italian labor was keeping the coal pits open and coal miners were starving. By the end of May, it was obvious that the strike had failed. When miners agreed to work under the hated pay cuts, the operators fired the Italian substitutes.

Animosity lingered and anti-immigrant hatred reached a climax in Church Hill on July 27. An angry mob of coal miners and supporters set fire to a boarding house that lodged immigrants. The rioters then attacked boarders fleeing the burning structure. They managed to kill one, Giovanni Chiesa. Several rioters went to prison, but the words “scab” and “Italian” were spoken in the same sentence for many years.

In the days after the collapse of the strike, some Italians found work as general labor in the mines. The railroads employed others. Although most of the high-value coal was gone by 1880, the area’s blast furnaces, limestone quarries and construction industries provided employment for Italian workmen, though often as contract labor under the thumb of an exploiting padrone, or labor boss.

The strikebreakers of 1873 were the first Italians to settle in the Mahoning Valley. They are our founding families. While records are sparse, a few Italian names from Church Hill’s coal camp days have survived: Giovanni Chiesa aka John Church, Michele Leopardo (Lopardo?), Martino Cereghino, Gaetano Cangiano, Rocco Cupola, Francis Marron (Francesco Marrone?), and Salvator Girard (Salvatore Girardi?). In the following years, heavy industry created demand for unskilled and semi-skilled labor. Thousands of Italians immigrated here to fill that need, despite their early exploitation in coal country. In the process, the newcomers created the large Italian American community of the Mahoning Valley.

It hardly seems possible that today’s suburban Liberty Township could have witnessed such contention and upheaval. Thanks to contemporary press coverage of the Coal Miners’ Strike of 1873, authors Joe Tucciarone and Ben Lariccia are able to document the arrival of the Mahoning Valley’s first Italians in their unpublished study: “The Coalburg Italians: Coal, Immigration, and Labor Strife in Ohio’s Mahoning Valley.”