Italy is no stranger to political activism. Both historic figures and current activists have changed the political and social landscapes of the country. Here, we remember two important figures who influenced change in Italy.

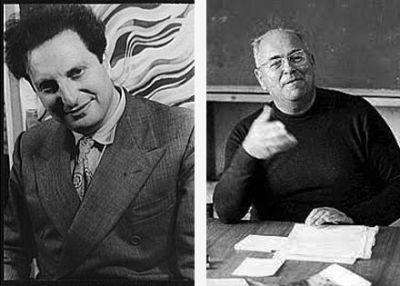

Danilo Dolci (1924-1997) was an Italian social activist, educator, and poet, opposed to poverty, social exclusion and the Mafia and a proponent of the non-violence movement in Italy. As a young architect visiting the ancient Greek ruins of Sicily in 1952, Dolci decided to visit what he called, “the poorest place I had ever known,” a fishing village in northwestern Sicily, Trappeto, just outside of Palermo.

“Report from Palermo” was published on January 1, 1959. It was a shocking and disturbing report on the corruption and poverty in Sicily that he had witnessed. The juxtaposition of the beautiful ancient temples and the horrid wretchedness of the poverty that he saw and experienced inspired him to write about it.

Towns like Trappeto had no electricity and running water. Their inhabitants were mostly illiterate and unemployed, and largely ignored by Church and State. Dolci worked with the people, learning their trades, and living alongside them to feel their struggle to exist. He started an orphanage there, organized co-operatives and began hunger strikes, sit-downs and demonstrations, all non-violent actions with the purpose of forcing the local and national government to do something to help these hopeless and desperate people.

From the mid-1950s to the late 1960s, Dolci used many techniques to get the attention of the government and help his many causes. A hunger strike drew attention to the poor in Partinico, with the goal of promoting the building of a dam over the Iota River to provide irrigation for the entire valley. To get the poor working and help fix the bad roads, Dolci began a “strike in reverse,” which meant they worked without pay, on unauthorized public works projects. He received the notoriety he had wanted, but he and his workers also got arrested. Defended by famous lawyers and supported by famous writers, he and his co-defendants were acquitted. Subsequently, he started another campaign for a dam in the Belice river by conducting another hunger strike in Roccamena in 1965.

He crusaded against the Mafia, got sued, was sentenced for libel, and got pardoned. He founded the Centro studi e iniziative per the piena occupozione, educating people on resolving conflicts with non-violence and training socially and politically committed young people.

Dolci was a cult hero in the U.S. and Europe, receiving the Nobel Peace Prize and the Lenin Peace Prize as well as numerous other peace and social awards. He was a passionate writer. His books are remarkable accounts and insights into the workings of society that have spurred change. This was aptly written as part of his obituary: “The man who in his youth studied architecture became an architect of social change.”

Carlo Levi, 1902-1975, was trained as a physician at the University of Turin, although he did not practice medicine and wanted to be an artist and a painter. In 1929, with Carlo and Nello Rosselli, he founded an anti-fascist movement called Giustizia e Libertà and was the leader of its Italian branch. Due to his political activism and anti-fascist beliefs, he was arrested by the pro-fascist government and exiled in the southern Italian region of Basilicata, known at the time as Lucania, historically one of the poorest, impoverished, and neglected regions of southern Italy.

This exile took Levi from 1935-1936, to Gagliano (Aliano) and later, Grassano, two remote towns that seemed to have been forgotten by time. There, he encountered a poverty that had been unknown to him and others in the prosperous north where he was raised. While living in those towns, he experienced la vita quotidiana of a people that kept old traditions and behaviors embodying medieval and pagan cultures that most modern Italians no longer advocated. He saved lives through his medicine, analyzed the fat, corrupt politicians, painted, and celebrated with the peasants in their colorful rituals and witchcraft, learning to appreciate their beauty and wisdom.

Levy’s paintings of the ragged, hopeless people with black, vacant eyes and the hauntingly desolate landscapes of the area, elucidates the tripartite theory of social inequality that he developed:

a) there are two separate societies, those in the cities and the peasantry, and the peasants always lose within a State in which they have no share or say or power.

b) economic poverty caused by impoverished lands, lack of industry, education, and health care.

c) exploitation by middle-class tyrants who over-taxed them and charged usurious rates for goods and services.

Though not a writer, Levi was so touched by what he found and experienced in his nearly two years in exile, that he wrote a memoir, “Cristo Si è Fermato ad Eboli.” Christ Stopped at Eboli, in which even God had forsaken the land and peoples of this remote area in southern Italy.