The greatest influence on the European world of art, economics, culture, and intellectual achievement was the Italian Renaissance. Florentine artist, Michelangelo Buonarotti, one of the most illustrious and well-known artists of this period, is perhaps most identified with his sculpture the “Pieta” in Rome’s St. Peter’s Basilica. Lesser-known are his other two sculptural pietas: the partially destroyed (by his own hands) Florentine Bandini Pieta and the unfinished Rondanini Pieta in Milan’s Castello Sforzesco.

Although there were descriptions of the Virgin Mary holding the dead Christ as early as 10th century Greece, the painted or carved image known as a ‘pieta,’ meaning pity or compassion, was popularized in late 14th century Germany, spreading to the Benelux Countries, France and eventually Italy. As devotion increased for the Virgin Mary, so did paintings and sculptures of her with Christ.

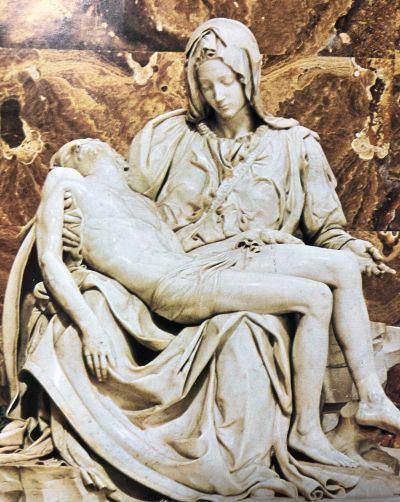

The German Pietas, which emphasize the brutality of what transpired in the Passion of Christ, elicit a powerful visceral response as opposed to Michelangelo’s cerebral approach, not wanting to mar perfection, downplaying traces of Christ’s ordeal by minimizing His gashes and holes. Mary’s youthful countenance is not fixed upon us or her Son, but inward, her left hand inviting us to behold man’s fall from grace had been redeemed through her Son’s death making possible eternal life.

Michelangelo was a sculptor, painter, poet, architect, and inventor. Due to his family’s ties to nobility, he had benefactors from the powerful Medici family and later the papacy. Living with the Medicis as a young man he was educated and influenced by premier artists of that time and studied under the famous sculptor Bertoldo di Giovanni. His mastery of anatomy was from the direct study of cadavers. When Lorenzo de Medici passed on in 1492 and Florence was losing power, he found himself in search of new patrons eventually leading him to Rome.

At the young age of 23, not yet well-known, he was contracted by Jean de Bilheres, Cardinal of Santa Sabina and French governor of Rome, to sculpt a life-size pieta for his tomb in the old Basilica of St. Peter’s chapel of Saint Petronilla, owned by the King of France. A liturgical as well as funerary function, it was placed in a niche above the altar. The contract dated August 27, 1498 read, “The said Michelangelo will make this work within one year, and...it will be the most beautiful marble that there is today in Rome, and...no other living master will do better.”

Michelangelo was a perfectionist thus, after the basic composition was made in rough sketches, finished drawings and clay models, he spent four months in the mountains of western Tuscany, Lucca, to find and quarry a flawless piece of white Carrara marble for the pieta. The finished pyramidal high-relief sculpture, 5 feet, 8.5 inches high by 6 feet, 4.75 inches base by 23.5 inches deep with its highly polished front and sides would then be placed in its niche.

“The greatest artist has no concept not already present in the stone that binds it, awaiting only the hand obedient to mind,” Michelangelo Sonnet-1538. As a religious man, his poetry uses the image of the sculptor’s art as a metaphor for body and soul. The block of marble being the body and the form emerging beneath the chisel representing the soul struggling to free itself from its material prison. He often wrote of his personal struggles with spirituality, sin, guilt, and redemption. His creations realize the capacity of a work of art to function as a sacramental object of devotion. The pieta is one of the “Seven Sorrows of Mary” used in Catholic devotional prayers.

“The true work of art is but a shadow of the divine perfection. Only God creates. The rest of us just copy,” Michelangelo.

From its initial location, the Pieta moved twice before 1749 when it went to the ornate Baroque Chapel on the north side aisle of St. Peter’s Basilica where it remains today. Far from its intended purpose, it must be viewed from a distance, high up and behind thick, bulletproof glass owing to its attack on the Feast of the Pentecost, May 21,1972. Hungarian immigrant to Australia, Laszlo Toth, took his geologist hammer to the Pieta and with 15 blows damaged Mary’s nose, left eye and cheek and severed her left arm at the elbow. He was 30-years-old at the time, matching the age of Christ at His death, yelling, “I am Jesus Christ risen from the dead.” Arrested and declared insane, he was sent to a mental hospital. The Pieta underwent a seamless 10-month restoration.

The only time the Pieta would leave Italy was to the 1964 New York World’s Fair’s Vatican Pavilion. With Gregorian chant playing, royal blue backdrop and illuminated by 400 flickering lights attached to a halo suspended above on strings, visitors on a moving walkway viewed the Pieta as Michelangelo intended with the sculpture inclined so Mary looked down upon them. Upon its return, Pope Paul VI declared it would never leave Italy again. My hope is that someday you are able to see its magnificence for yourself.