Il lavoro a contratto, una forma di traffico di esseri umani, ha una lunga storia sul suolo degli Stati Uniti. In passato, molti dei nosti immigrati sono stati coinvolti in questo sistema di lavoro sotto un “padrone”. Le radici di questa pratica sono legate alla situazione dei contadini in Italia ed ai gravi problemi economici nel Meridione che fecero seguito l’unificazione del Paese nel 1861. Tra questi, la mancanza di terreni e posti di lavoro per la popolazione in crescita ed un ingiusto sistema di tassazione che favoriva il Nord in via di sviluppo ai danni di un Sud ancora agricolo. All’indomani dell’Unità, i contadini persero il diritto di usare campi e pascoli comunali, mentre la riforma agraria del paese non riuscì ad assegnare loro un appezzamento sufficiente a mantenere una famiglia. Queste condizioni portarono ad una rivolta contadina nel meridione che si tramutò in banditismo diffuso, a cui fece seguito una dura repressione dal governo. Per sopravvivere, molti italiani immigrarono, prima in Sud America e poi negli Stati Uniti e in Canada. Parte 2.

Contract labor, a variety of human trafficking, has a long history on U.S. soil. Does your family’s story hold a memory of an ancestor who “was put to work in America,” made landfall in a large group to serve under a padrone or labor boss or paid a bossatura an under-the-table job tax? If so, this piece may offer some insights about the subservient status of a large group of Italians who arrived during the great wave of European immigration.

The padrone system continued through the 1880s, as Italians and Chinese arrived indebted to labor brokers or under the control of bilingual foreman, padrones who gathered their recruits into work gangs that often competed with native workers or in areas where labor shortages occurred. The arrival of so many immigrants of non-Nordic countries alarmed the early U.S. labor movement. Unions suffered from the use of immigrants as strikebreakers. In 1870, mine owners in Akron seriously contemplated the use of Chinese to keep struck mines open. The widespread coal miners’ walkouts in Ohio and Pennsylvania in 1873 and 1874 had seen Italians successfully used as replacements.

In its June 1, 1882 edition, the New York Daily Tribune reported that 5,518 Italian immigrants had arrived at the Castle Garden depot, precursor to Ellis Island, during May of that year. On the West Coast at the start of the 1880s, roughly a quarter of California workers were Chinese, many of whom were employed under a form of contract labor. The specter of an invasion of foreign, compromised workers undermining prevailing wage rates and work norms caused public outrage. Moreover, the abuses of the padrone system exacerbated racial animosity. Asians and Southern Europeans, in the view of many, did not deserve a permanent role in an America originally designed for white, Protestant, English-speaking citizens.

The public demanded protection from the abuse of foreign workers and cries for banning immigrants from certain countries appealed to many. In 1882, Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act. Three years later, new legislation prohibited U.S. citizens and businesses from hiring contract labor. A series of amendments to the 1885 law further strengthened the government’s war against the padrone system. But as long as the demand for cheap, exploitable labor remained and as shipping lines and their ticket agents continued to profit from emigration from Italy and from other sources of cheap labor, the pool of indebted immigrants continued to grow. Again, in 1888, the continuing scandal of the contract labor system became the subject of a House of Representatives select committee. Four years later, a report to the U.S. Senate detailed the exploitation in Italian immigration to America.

The subagents paid runners from one to five francs for each passenger they brought in. Joseph Powderly, U.S. Commissioner of Immigration, 1892.

The push was also on to severely limit immigration from Southern Europe. It achieved long lasting results. In 1924, Congressman Albert Johnson and Senator David Reed introduced and helped pass an act of Congress that drastically reduced immigration from southern, central and eastern Europe. As one of the targets of the legislation, immigrants from Italy had already been in the crosshairs of anti-immigrant bigotry.

What were the provisions of the Immigration Act of 1924? The legislation capped yearly immigration to 2 percent of a nationality’s numbers in the 1890 census. As with many laws that are discriminatory in nature, its creators hid their intent behind mathematical formulas. Without even mentioning the word “Italian,” the law severely restricted the flow of new immigrants from Italy. To configure their quota, the formulators fixed 1890 as the deciding year since Italians began to enter in larger numbers only later. Thus, while the Chinese had been specifically excluded from immigrating, the Italians came under a severe, partial ban that would remain in effect until 1968.

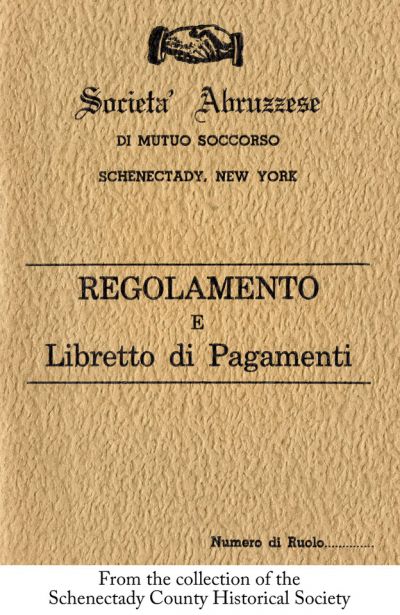

The Italian immigrant community itself responded to the conditions that fed the padrone system. Groups like the Società Abruzzese in Schenectady and the Fraterna Società in Youngstown, organized within the Italian enclaves to protect the interests of their countrymen. Immigrants paid dues and received a regolamento or membership booklet that entitled them to sickness, burial insurance and other benefits. Connections to the prominenti within the fraternal societies provided members with a network of contacts for jobs. Italian parishes and settlement houses like Youngstown’s Our Lady of Mount Carmel Church and the Pearl Street Mission also supported a population in need of skills useful for finding a job. In 1900, New York City boasted one hundred settlement houses that educated its multinational immigrant communities in the ways of American culture and the English language.

With more knowledge, experience and second language skills, Italian immigrants in the United States increasingly avoided the padrone system and indebtedness to shipping agents. Immigrants established their own businesses: construction companies, restaurants and grocery stores. Moreover, through savings, they could independently finance their relatives’ passage to America. By 1930, the padrone system, at least for Italians, was gladly a thing of the past.