On the morning of December 7, 1941, Japanese planes bombed Pearl Harbor – a U.S. naval base on the island of Oahu – destroying or damaging 18 ships and over 300 aircraft and killing or wounding almost 3,500 Americans. The next day, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed a declaration of war against Japan.

A year earlier, when Japan signed the Tripartite Pact with Germany and Italy creating the Axis Powers, its relations with the U.S. had already been deteriorating. Japan had been aggressive in its dealings with other countries and in retaliation, the U.S. was considering further trade restrictions on the materials Japan needed. One year before the Tripartite Pact was signed, Germany invaded Poland causing France and Great Britain to declare war on Germany, the start of WWII. With the attack on Pearl Harbor, the U.S. entered WWII and Italy became the enemy.

Italian immigrants have been a part of America since the beginning of European colonization, but for each year from 1896 to 1917 and in 1920 and 1921 – according to U.S. Immigration Statistics at Ellis Island – Italian immigrants were the largest of all ethnic groups to arrive in America. Up to half of those immigrants returned to Italy, but for those who stayed, the path was not easy. Italian immigrants were the target of rampant discrimination, unlawful labor practices, religious intolerance, and unsanitary housing conditions. Additionally, they were viewed as having criminal connections. When the U.S. entered WWII, over 600,000 persons of Italian descent became enemy aliens.

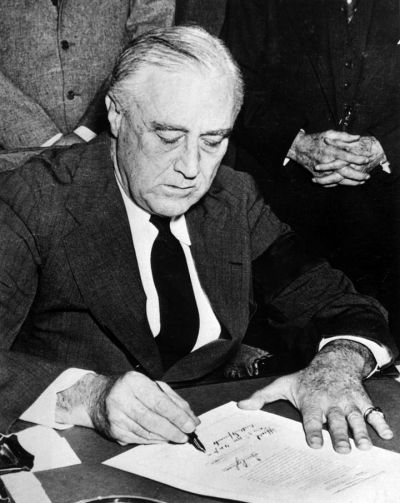

On December 8, 1941, President Roosevelt signed Presidential Proclamation 2527, stating “all natives, citizens, denizens or subjects of Italy being of the age of fourteen years and upwards who shall be within the United States or within any territories in any way subject to the jurisdiction of the United States and not actually naturalized, who for the purpose of this Proclamation and under such sections of the United States Code are termed alien enemies.” (Japan and Germany were addressed in separate proclamations.) Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066 – signed February 19, 1942 – authorized the Secretary of War, “in his discretion” to “prescribe military areas” where a person may be excluded or subject to restrictions.

After the end of WWI in 1918, even though armistices and peace treaties had been signed, many countries sensed an uneasiness as political, economic and social turmoil was felt throughout the world. In preparing for another “global conflict” the Federal Bureau of Investigation had compiled a list of “communist, fascist, or subversive individuals or organizations.” As soon as Roosevelt declared war against Japan, the FBI began targeting those they had labeled “enemy aliens.”

Italians were taken into custody, had their homes raided, were ordered to move from their homes, lost their jobs, had personal property confiscated, were restricted from traveling, and forced to register as enemy aliens. Internment camps – some later became POW camps – were located throughout the country, but many Italians were sent to Fort Missoula in Montana.

On Columbus Day, October 12, 1942, “in recognition of the fact that Italian immigrants and citizens were loyal to the United States, the enemy-alien restrictions were lifted for those of Italian ancestry;” however, many who had been interned or excluded were still held. WWII ended on September 2, 1945 and soon after President Harry S. Truman – Roosevelt had died in April 1945 – signed two proclamations removing additional restrictions pertaining to “enemy aliens.”

In 2000, Congress instituted an act for “a Government report detailing injustices suffered by Italian Americans during World War II.” Known as the “Wartime Violation of Italian American Civil Liberties Act,” it required the U.S. Attorney General to “conduct a comprehensive review of the treatment by the United States Government of Italian Americans during World War II.”

The Department of Justice report, dated November 2001, “addresses arrests, detentions, internments, the exclusion of individuals from military zones, the imposition of curfews, raids on homes, the confiscation of property, and the effects on fishermen and railroad workers, all within the context of wartime orders, proclamations, and directives.” The report provides “details how actions by the federal government immediately prior to and during World War II affected thousands of persons of Italian ancestry residing in the United States.” The report was prepared “to bring these events to light and to clarify the historical record.”

Department of Justice Report: A Review of the Restrictions on Persons of Italian Ancestry During World War II, Congressional Report: https://www.schino.com/pdf/italian.pdf