L'articolo descrive i viaggi di Marco Polo e Matteo Ricci verso l’est. Nel 13esimo secolo, Marco Polo viaggiò in India, Birmania, e Sud-est asiastico per la maggior parte del tempo in Cina. Iniziò il suo viaggio lungo la Via della Seta nel 1271 con il padre e lo zio. Passarono 3 anni prima che arrivassero nei paesi asiatici. Dopo 17 anni, tornarono a Venezia con le storie delle loro esperienze soprattutto della dinastia Yuan, di cui Polo ne fu un rappresentante.

Nel 1582, Matteo Ricci, uno studente delle scuole Gesuite Italiane, viaggiò in India e in Cina. Fu un missionario Cristiano durante la dinastia Ming. Durante la sua permanenza in Cina, creò la prima mappa con la Cina e l’ampiezza del suo potere. I Cristiani cinesi amarono Ricci. Quando Matteo morì, fu sepolto a Pechino nonostante gli stranieri non potessero nemmeno entrare in città. Ricci, invece, ebbe il grande rispetto degli imperatori.

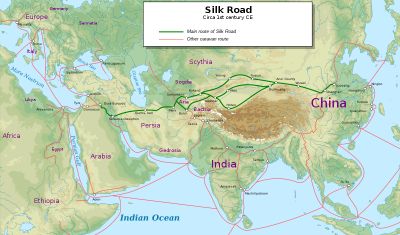

In the 13th century, east-west trade was between China and Europe. The Silk Road, sometimes referred to as the Silk Route because of its numerous passageways, was the connection between the territories since the second century BC. Fifteen hundred years later, the Silk Route provided the path for a Venetian merchant to bring Asian culture to Europe, and 300 years after that, for an Italian Jesuit Monk to bring Christianity to China.

Marco Polo started his journey east in 1271, with his father Niccolo and his uncle, Maffeo. The brothers had established a successful trade business in Asia and met in the mid-1260s in Dadu (now Beijing) with Kublai Khan, the grandson of Genghis Khan, founder of the Mongol Empire. Khan was forming the Yuan Dynasty (1271 to 1368) and asked the brothers to deliver a message to the pope, requesting educators of Christianity.

When Niccolo and Maffeo began their second trip east, with teenaged Marco, it took over three years to travel the Silk Route. The two priests who accompanied them did not complete the journey. In Venice, Marco received an education that included the mercantile business, and during the journey he quickly learned the customs and languages of the cities they passed through. When the three reached the summer Capital of Xanadu (Shangdu), Kublai Khan was impressed with Marco’s skills and appointed him an envoy.

Marco traveled throughout India, Burma and Southeast Asia and extensively throughout China for 17 years as a representative of the Yuan Dynasty. Upon his return, he shared stories of his adventures with Kahn, enlightening the ruler about the land, people, and customs of the Mongol Empire.

The Polos left China in 1291, traveling by sea around India, and reached Venice in 1295, during the Venetian-Genovese Wars (1256 to 1381). Marco joined Venice in its fight against Genoa and, in 1296, was captured in a battle at sea and imprisoned. In jail, he dictated his travel accounts to a cellmate. “The Travels of Marco Polo” was widely received, but not without its skeptics.

Born into a family of wealth and political affiliations, Matteo Ricci was nine when he began an education in a Jesuit school; at 16 he studied theology. After he joined the Jesuit Order, he traveled to India and in 1582 (during the Ming Dynasty, 1368 to 1644), he began missionary work in China. Previous attempts to bring Christianity to China had not been successful.

Ricci utilized the Jesuits’ approach to education by learning about the culture of those being taught: his students were Chinese scholars. In 1601, Ricci was the first Western European granted access to the Forbidden City (in Beijing), the imperial palace of the Ming Dynasty. Working with Jesuit and Chinese scholars, the following year he created the first map with China located in the center of the world.

With his education in astronomy, geography and mathematics, and his interest in Chinese culture, Ricci was accepted by Chinese intellectuals who embraced Christian philosophy. He adapted to his surroundings, learned Chinese and studied Confucianism, comparing it to the principles of Christianity. His first book, “The True Meaning of the Lord of Heaven,” equated the similarities. Although widely received, it was not without skeptics.

Both Marco Polo and Matteo Ricci transformed the culture of China and Europe beginning in the Late Middle Ages to the Early Modern Period in world history. Marco Polo shared the stories of the people of the huge Mongol Empire and brought Asian culture, along with the concept of using paper for money, to Europe. Polo’s travels inspired exploration, including the journeys of Christopher Columbus. Although buried in Venice, Polo’s tombstone vanished during reconstruction of the Church of San Lorenzo.

Matteo Ricci died in Beijing in 1610. Rules of the Ming Dynasty prohibited foreigners from being buried in the city, but at the special request of the Jesuits, the emperor allowed Ricci to be interred in a Buddhist temple on the west end of the city. Ricci is credited for bringing the foundation of Christianity to China and for further introducing the cultures of the East and the West to each other.