Joey Giambra, un italo-americano che abitava in Buffalo, è morto per il COVID in maggio. Giambra era un uomo rispettato nella città per molte ragioni. Lui era un poliziotto, uno scrittore, un poeta, un drammaturgo, e un musicista. Era un'icona in Buffalo, dopo aver lavorato vent’anni nella polizia, ha cominciato il libro è “La terra promessa” che parla dell’esperienza di immigrati italiani. Lui aveva anche inciso un CD della sua musica chiamata “I love you Buffalo”. La sua musica era popolare tra i suoi amanti. Il suo capolavoro è un libro intitolato “The hooks”. In questo libro, parla della vita difficile per gli immigrati italiani, descrive come gli italiani dovevano lavorare duramente ma che non hanno mai dimenticato mai di onorare le feste italiane, specialmente la festa di San Antonio. Per queste ragioni, nella comunità di Buffalo sono molto tristi per la morte di Giambra perché era un uomo molto bravo.

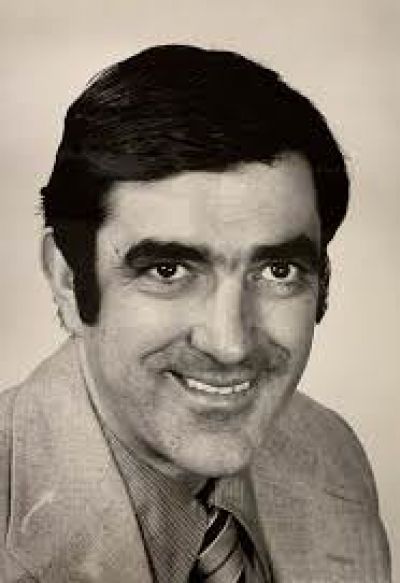

Beloved Buffalonian Joey Giambra recently succumbed to COVID-19. He was hospitalized at the Buffalo General Medical Center on April 25 and, sadly, passed on May 14, 2020. He was 86 years young, creatively sharp, congenially engaging, and will be sorely missed by the Buffalo community and beyond.

Buffalo’s Joey Giambra is one of the city’s favorite sons and a first-generation Italian American, connecting the past from the Lower West Side into our present and future living contexts through his music, drama, poetry, and writing. Giambra was an Italian icon, an ambassador of understanding, and his flourishing artistry had no end to his talents as did his affection for all peoples; a rare, spiritual quality that few possess.

Giambra had an inviting and contagious smile; one he magically wove into an incredible sensitivity and a literary love for culture and the goodness in people. He made an indelible impression, stirring and inspiring you with energy, spirit and the promise to do better. “I am saddened to hear of Joey Giambra’s passing. His contributions to Buffalo’s music and theater community will be felt for years to come,” announced Buffalo Mayor Byron Brown.

To his greatness, Giambra envisioned and ambitiously lived out five careers in one remarkable lifetime, it seems, in addition to the important roles of dedicated father and husband. In 1963, he joined the Buffalo Police Department and served for 20 years as a police officer and sergeant before retiring as a detective. At 44, Giambra would earn a bachelor’s degree in criminal justice from SUNY Buffalo State. He was a self-taught jazz trumpeter, a pianist, an actor, a singer and songwriter, a former restaurant owner, a filmmaker, a poet, an Italian chef, the author of four books, a historian, a one-time candidate for mayor of Buffalo, he spoke fluent Sicilian, and he possessed endless bundles of creative energy to expend.

Giambra briefly spoke about his 20-year service as a member of the Buffalo Police Department in an interview with Maria Scrivani, a writer for the Buffalo Spree magazine: “When I became a detective in plainclothes, they wanted me to keep tabs on the Mafia. I never framed anybody. That would have been easy to do in narcotics where I was working, then. I never took money. I only fired a gun three times, and they were warning shots.”

Giambra’s long writing career included “La Terra Promessa,” a documentary that insightfully chronicles the Italian America immigrant experiences in Western New York in the early 1900s. His earlier work entitled, “Bread and Onions,” published, in part, by the Per Niente magazine of Buffalo, edited by Joe DiLeo and Giambra, did inspire him to produce “La Terra Promessa.”

His many movie appearances included such films as “Hide in Plain Sight,” “Buffalo ’66” and “Marshall.” In 1978, Giambra recalled to Scrivani: “When ‘Hide in Plain Sight’ was being shot in Buffalo, I had a chance to read for the producers. Then, they had me read for James Caan. They cast me as a cook in my own restaurant.”

In 2017, Giambra looked to the future with optimism about his artistry as a playwright and actor announcing, “What I want to do next is to direct my play, ‘No One Is Us,’ on stage right here in Buffalo. And cook and bake. It kills me to pay three dollars for a loaf at Wegman’s when I can bake it for thirty-three cents. Whatever I’ve done in life, I have trusted my art – that’s what keeps me going.”

Giambra also produced a recorded CD, entitled, “I Love You, Buffalo,” in his debut as a vocalist. Mayor Brown noted that the work is now part of the city's sesquicentennial time capsule at Buffalo’s City Court plaza remarking, “This is a lasting legacy and remembrance of Joey Giambra for future generations.”

Poignantly, Giambra writes about “The Hooks,” a waterfront ghetto where Italians arrived and lived in downtown Buffalo in the early 1900s. Giambra writes in Per Niente magazine, excerpting from his work “Bread and Onions” this horrible and despairing depiction: “To escape stigmatic welfare, men shoveled snow and concrete and dug ditches. They ate bread and onions, pasta and lentils, drank wine, got old, and waited to die…The Hooks were old, ghostly and dilapidated, and would soon perish. Politicians promised renewal but none came. As the Depression ended, businesses closed or moved, as did many families.”

Despite the pain of the times, the arriving Italians still had the summer’s Feast of Saint Anthony to look forward to. Giambra’s accurate descriptions still live on and are retold from generation to generation. “A marching band played to great applause, no emotional restraint, Sicilian veneration. Men, women, and children: Americans of the first generation carried banners and a huge statue of Saint Anthony past wooden-framed homes. Multi-colored lanterns adorned windows and front porches…They were transformed into stunning, candle-lit altars. Hanging in a backdrop of embroidered linen were the flags of America and Italy.”

The Italians then moved to congregate on the sidewalk in front of Saint Anthony’s Church, recalls Giambra, “Spiritually unified people knelt in prayer. Devotion was the rule, the highest example…Fireworks lit up the sky, a pyrotechnic blizzard, the last night of the feast, the final goodbye.”

Giambra was born in 1933 on Georgia Street on Buffalo’s Lower West Side. The cultural and colorful descriptions of the early Lower West Side were insightfully created through the cultural and environmental lens from his Georgia Street home and neighborhood. Those beautiful words provide cultural clarity and a bridge to understanding the Lower West Side the way Giambra vividly and eloquently describes it. His great literary works are part of the city’s annals for appreciation now and for posterity.

“His family recalls that he received his early passion for music and drama from Anne Rodenhoffer, an elementary school teacher at the old Public School No. 2. He went on to Hutchinson Central High School where he formed a band that maintained a steady business at weddings, parties, and other events,” writes Sean Kirst in the Buffalo News.

“We, the many, many people he loved and touched, are left with a big hole in our lives. For me, there will always be something missing,” painfully writes Tom Naples, his old friend, a guitarist who often worked with Giambra.

Giambra is survived by his wife of 66 years, Shirley, a son and grandson, Gregory Sr. and Gregory Jr., and he was preceded in death by a daughter, Michele.