The term “Scapigliatura” refers to an interdisciplinary art movement born in Milan in the post-Risorgimento period. The word itself (translated into English as “dishevelment” but perhaps closer in meaning to “bohemianism”) was first defined in an 1862 novel written by Cletto Arrighi (1828-1906) titled La Scapigliatura e il 6 febbraio. The novel recounts the story of a failed Milanese revolt against Austrian oppression in 1853. Among the traits of a scapigliato as defined by Arrighi, are “…revolt and opposition to all established order.” He goes on to elaborate upon the subtleties of Scapigliatura thinking stressing that “…hope is its religion; pride its uniform, poverty its essential character.”

Arrighi’s description put into place most of the ideas central to Scapigliatura comportment: individualism, bohemianism, anti-authoritarianism, and revolutionary zeal contained within a personality of excessive and anarchic behavior. Most members of Scapigliatura died young, many taking their own lives, while others fell prey to poor health, bad luck, and poverty.

Among the most important members of the movement, in addition to Arrighi, were the writers Giovanni Rovani (1818-1874), Emilio Praga (1839-1875), and Iginio Ugo Tarchetti (1841-1869); the poet/composer Arrigo Boito (1842-1918) and his architect brother Camillo (1836-1914); the painters Tranquillo Cremona (1837-1878) and Daniele Ranzoni; and the sculptor Giuseppe Grandi (1843-1894).

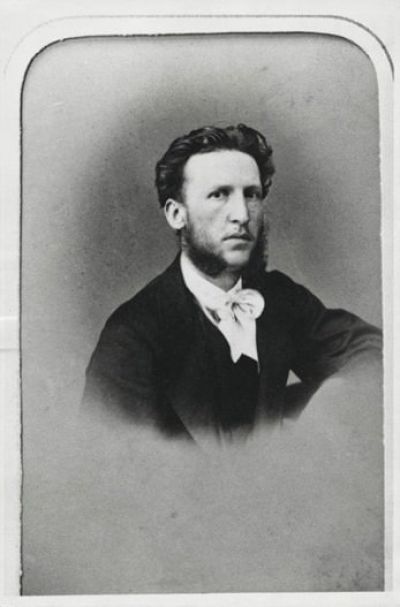

Iginio Ugo Tarchetti (the pseudonym of Igino Pietro Teodoro Tarchetti, (1) born San Salvatore Monferrato 1839, died Milan 1869) was a seminal literary figure in Scapigliatura. A poet, novelist, journalist, and translator, he was among the first in the group open to the foreign influences of writers like E.T.A. Hoffmann (1776-1822), Mary Shelley (1797-1851), Edgar Allan Poe (1809-1849), and Charles Baudelaire (1821-1867).

The two sonnets that appear below bear the same title, Nel dì dei morti, and were published in a posthumous collection of Tarchetti’s poetry titled Disjecta: Versi, (Fragments), (Zanichelli, Bologna, 1879). The sonnets first appeared in November 1867, in the magazine L'Illustrazione universale (IV, 213, 28 novembre 1867). They appeared again in the journal Il Presagio: Strenna del 1868 (Bontà and Co., Milan, 1868). It was in this latter publication that a place and date for the compositions were cited: “Milan, November 1, 1867.” The sonnets were written on All Saints’ Day, preceding the commemoration of the dead on the day to follow, November 2 or All Souls’ Day.

Space in this brief essay does not allow for an extensive analysis of the influences and imagery in these two important poems by Tarchetti. In both, the poet has entered a landscape of the dead – the cemetery where his father’s tomb is located. It is a mild autumn day, a lovely day in fact, were it not for the dark ruminations upon which the poet fixates. Slowly, as in the stories and poems of Poe, a malaise is felt. The poet’s meditations dwell upon burial itself, the eternal silence of the dead, and thoughts on the chronic unhappiness that had characterized his father’s life. Such macabre themes were an integral part of both Tarchetti’s writings specifically, and Scapigliatura thinking generally.

The second sonnet stresses and explores many of the same themes and motifs as the first, heightening the emotional impact in places. It becomes a dialogue between the poet and his deceased father. While no response is forthcoming from the grave, through the poet’s act of remembrance, embodied in the last rays of the setting sun and the smile of nature, solace and comfort may still be possible for those who remain.

Many of the Gothic elements present in these two poems would be expanded upon in Tarchetti’s more famous collection of short stories Racconti fantastici (1869) (his first work translated into English) and his novels Paolina (1865) and Fosca (1869).

Like so many of his Scapigliatura friends and colleagues, Tarchetti’s life ended prematurely. He died of tuberculosis at the age of 29 in 1869. His imaginative works, however, would go on to influence such 20th century Italian writers as Dino Buzzati (1906-1972) and Italo Calvino (1923-1985).

(1) Tarchetti’s baptismal certificate indicates that Igino Pietro Teodoro Tarchetti was born on June 29, 1839, in San Salvatore Monferrato, a village in the Piedmont. The confusion over his name started in infancy: on the certificate, “Igino” is scrawled in to correct the form “Iginio,” which had been written first. Tarchetti later preferred the error, “Iginio,” to grace his letters and publications. (See: L. Venuti, “The Hyena’s Laugh: I.U. Tarchetti and the Birth of Italian Gothic,” Los Angeles Review of Books, December 4, 2020.

www.lareviewofbooks.org/article/the-hyenas-laugh-i-u-tarchetti-and-the-birth-of-italian-gothic/

|

NEL DÌ DEI MORTI Il morire è nulla; è il non vivere che riesce orribile. I. Suonano a festa: olezzan di viole Inverno riede; Autunno, come suole,

II. Che felice non fosti! È questo ingrato Ma dimmi, per le lacrime, che dato Ma tutto è muto! - Il sol dall’alto sferra |

IN THE DAY OF THE DEAD Dying is nothing; it is not living which is horrible. I. They play to party: smelling of violets Winter stands; Autumn, as usual,

II. How happy you weren't! And this ungrateful But tell me, for the tears, given But everything is silent! - The sun from above unleashes |