Giovanni Paolo Panini e Giovanni Battista Piranesi furono due degli artisti più bravi durante il diciottesimo secolo. Questi artisti dipinsero la città di Roma. Panini nacque a Piacenza. Fu fortemente affascinato dall’architettura romana e dalla geografia della città. Panini è conosciuto per il suo dipinto “Vedute” che mostra i posti più iconici di Roma per esempio il Colosseo, il Foro Romano, e La Basilica di San Pietro. Piranesi nacque vicino a Venezia. Quando arrivò a Roma, lui venne ispirato dagli edifici, dai monumenti, e dalla storia antica. Quindi, iniziò a dipingere queste immagine. Grazie a questi due uomini, oggigiorno abbiamo un buon senso di com’era Roma durante questi tempi.

Giovanni Paolo Panini (1691-1765) along with Giovanni Battista Piranesi (1720-1778) were the two greatest and most celebrated 18th century artists devoted to depictions of Rome. Panini was born June 17, 1691 in Piacenza. Originally destined for a career in the Church, he soon turned his attention, like Piranesi, to the study of architecture. Arriving in Rome in 1711,

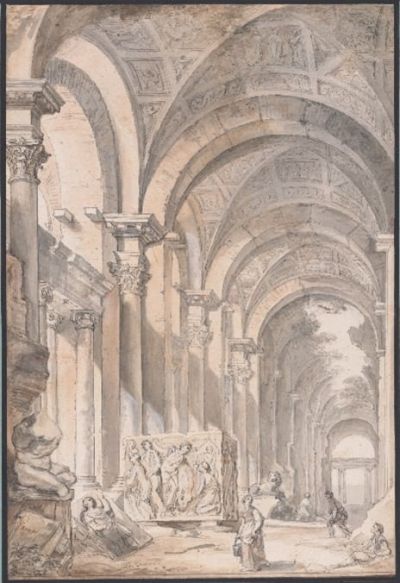

Panini also studied drawing and was known as a painter of landscapes, fresco decorations and architectural views. Panini’s talents and interests were far-ranging, but his reputation was forever established as a painter of Roman views (vedute) both accurately rendered and imaginary. Unlike the more romantic images of Piranesi, Panini’s paintings tended to record the most famous sites of the city and as such his work was in great demand by many 18th century Grand Tourists (especially the British) who flocked to the city.

Vedute depicting identifiable places or buildings such as the Roman Forum, St. Peter’s Basilica or the Colosseum, were often realized as part of the artists’ desire to create a catalogue

of the city’s most famous monuments. Despite the architectural accuracy of the buildings depicted, however, they were often placed within imaginary and picturesque settings. As a result, vedute appeared in two forms: vedute prese da i luoghi, meticulously rendered views of specific places; or vedute ideate, fictitious views combined with authentic buildings that mixed the real and the imaginary to create a capriccio. Both types were popular with the many foreign travelers wishing to visually document their journeys.

Giovanni Battista Piranesi was born October 4, 1720 in Mogliano near the city of Venice. Piranesi’s education as a young man included the study of classical languages, Roman history and the writings and buildings of the great architect Andrea Palladio (1508-80). His aspiration to become a great architect would never be realized. Instead, with his arrival in Rome in 1740, he became one of the most important and prolific illustrators of that city’s ancient monuments. Piranesi’s drawings, prints and book illustrations depicting the monuments of ancient Rome and their ruins, like Panini’s, were among the most popular and sought-after images on the Grand Tour. Combining archeological precision with imaginative settings, fantastic juxtapositions and inventive viewpoints, Piranesi’s art was a dazzling visual testament to the evocative power of art, architecture, history, and the longing for the past.

Eighteenth century Rome looked quite different from the city we know today. New building programs supported by the power and wealth of the Papacy existed side-by-side with the crumbling and pillaged monuments of antiquity. Already by the Middle Ages, the Roman Forum between the Capitoline Hill and the Colosseum was so overgrown that it was referred to as the Campo Vaccino or “cow pasture.” The theme of the struggle between ancient ruins and their return to nature resides at the heart of both Panini’s and Piranesi’s most powerful work.

After residing in Rome for three years Piranesi wrote, “no buildings of today display the magnificence of the old, such as the Forum of Nerva, the Colosseum or the Palace of Nero – nor is here a prince or private man inclined to create any such.” Along with Panini’s great interior view of the Pantheon, Piranesi’s view of the interior of St. Peter’s Basilica demonstrated the dialogue between past and present so much at the heart of the Grand Tour.

No structure better evoked “the grandeur that was Rome” than the Colosseum. Fraught with meaning and significance through many periods of history, the ruins of the Colosseum embodied the very essence of lost empire. Edward Gibbon, on the Grand Tour between 1763 and 1765, recalled the exact moment when he decided to write “The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire,” “It was at Rome on the 15th of October 1764 as I sat musing amidst the ruins of the capitol…that the idea of writing the decline and fall of the city first started to my mind…”

The evocative and romantic interpretations of ancient Rome and its lost grandeur depicted by Panini and Piranesi often surpassed the real thing in the eyes of many Grand Tourists. Goethe, for example, ultimately complained that the Baths of Caracalla and Diocletian did not live up to Piranesi’s views of them.

https://www.lagazzettaitaliana.com/history-culture/9771-eighteenth-century-views-of-rome-the-art-of-giovanni-paolo-panini-and-giovanni-battista-piranesi#sigProIdd766ef6f1f