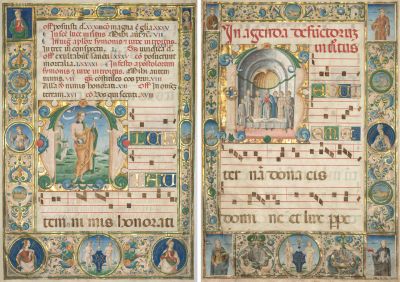

Two magnificently illuminated manuscript pages are preserved in the Cleveland Museum of Art. Their dimensions and style of decoration indicate that they were detached at some point in their history from an important set of choir books. Indeed, a coat of arms prominently painted in the lower margin of each leaf reveals that they were commissioned by Bartolommeo delle Rovere for Ferrara Cathedral. Delle Rovere was Bishop of Ferrara from 1474 to 1494. His coat of arms features a shield bearing a rovere (oak tree) surmounted by a patriarchal cross, the symbol of his rank and authority, and also signifying his status as Patriarch of Jerusalem. Bartolommeo was the scion of a famous family that included Pope Sixtus IV. The extent of their decoration indicates that the two leaves (or pages) must have been part of a large set of choir books that would have been expensive and time-consuming to produce.

A variety of music manuscripts were used throughout the Middle Ages and Renaissance for the practice of the Christian liturgy and the singing of the Daily Office. Made from parchment (animal skin), not paper, they were copied by a scribe and then decorated by specialist artists, called illuminators. These choir books were generally large enough to be used on a lectern and viewed simultaneously by the members of a choir. Every church, chapel and community of monks or nuns needed at least some choir books, without which the elaborate services could not take place. Because of that large demand, copying and “noting” (supplying the music) of manuscripts went on continuously throughout Europe, even beyond the invention of printing. The noting of service books, an arduous task requiring great care and precision, is an expense often found in medieval accounts. Wealthy ecclesiastical foundations could afford to embellish their choral books with sumptuous illuminations and decorated letters and often attracted the most talented illuminators for this purpose. Unfortunately, many manuscripts were dismembered in later centuries by avid collectors or looted by Napoleonic troops.

The two main types of choral books in the Middle Ages and Renaissance were the Gradual, which contained the musical parts of the Mass, and the Antiphonary, which contained the music for the Daily Office (Matins, Lauds, Prime, Terce, Sext, Nones, Vespers, and Compline). All churches were expected to have a Gradual and an Antiphonary, always made in several volumes to cover the entire liturgical year, and all monasteries were certain to own them as well. Their music was generally plainsong or Gregorian chant. The origins of liturgical music are traditionally said to go back to St. Gregory the Great (d. 604) who is credited for recording the principles of Gregorian chant.

These liturgical books were normally stored horizontally in book chests and book cupboards. Small tabs at the head and foot of the spine facilitated the removal of a book by pulling it, spine first, from its chest. The production of books before the invention of printing was labor-intensive and costly. For this reason, books continued to be prized throughout the Middle Ages and Renaissance. Given their value, many books were actually chained to the lecterns or tables where they were intended to be used.

Further investigation has shown that the two leaves from Ferrara Cathedral, now in Cleveland, were part of an enormous set of 21 volumes of a gradual. These were enormous books measuring some 30 by 20 inches and weighing up to 60 pounds. Their weight probably required two people to lift. Payment records indicate that they were illuminated by Jacopo Filippo Argenta, who labored on their decoration from 1478 to 1486. One of the leaves introduces the chant for the Introit to the Mass for the Feast of St. Andrew, celebrated on November 30 and marking the beginning of Advent in the liturgical calendar. The second leaf depicts a large Initial R for the words Requiem eternam. This marks the opening of the Office of the Dead. The initial features a scene with a priest surrounded by acolytes standing over the deceased.

In an era that placed great emphasis upon refinement of taste, panoply and grandeur, as well as artistic erudition, Renaissance popes – more than those of any other period – lavished great expense in commissioning some of the most elegant and sophisticated illuminated manuscripts of their day. So, too, did high-ranking members of the clergy such as cardinals and bishops. The embellishment of such books was just as important in the projection patronage as were sumptuous vestments and liturgical vessels. Bartolommeo delle Rovere, being a scion of an important family and the nephew of a pope, understood this patronage. His coats of arms appearing throughout his gift of choir books to Ferrara cathedral reflect this tradition.

Ferrara, with its broad streets and numerous palaces dating from the Renaissance, is one of Italy’s most attractive towns located in the north in Emilia-Romagna. As many travelers to Italy will know, Ferrara is a city of great beauty and cultural importance. The city’s cathedral still stands as a beacon of Renaissance and Baroque taste. With a little imagination, we can see delle Rovere’s beautiful choir books on a high lectern and we can hear the choir singing their chant from its pages.