Tra la fine del 1800 ed il primo ventennio del ‘900, per milioni di Italiani prevalentemente contadini origanari del Meridione della penisola, la parola America diventò quasi magica: la terra delle promesse, il sogno metropolitano, la modernità, la democrazia, il lavoro. Un mito alimentato dalla certezza di trovare un impiego, dalla speranza di una vita migliore, dal riscatto sociale, dall’impossibilità di rimanere in un’Italia incapace di offrire vie di fuga dalla fame e dalla miseria. È importante separare la realtà dai frequenti equivoci e malintesi associati con l’immigrazione italiana negli Stati Uniti.

"Genealogy is the second most popular hobby in the U.S., after gardening," says Time Magazine. Italian Americans are certainly second to none in pursuing this pastime that entails careful research and the sharing of results. There's a lot of satisfaction in finding a lost relative or bringing to light a family story that somehow disappeared years ago. Therefore, situating that story and those ancestors in the events and spirit of the times is important. In fact, being knowledgeable about the historical period in which your ancestors lived will aid in the research itself. What are some common misunderstandings about the years 1870-1924, when most of our Italian ancestors arrived in the U.S.?

- Once they came, they stayed. Before WWI, almost 50 percent of Italians repatriated. For this reason, when constructing your family tree, it's important to be aware that your history in the U.S. may be older than you think. At the beginning of the period, most of the immigrants were men. In fact, this group was called "birds of passage" because of their repeated trips to the U.S. Your grandfather's father or his uncles and cousins may have arrived and left before the arrival of later family members who settled in the U.S.

- They settled in cities. In fact, Italians settled wherever they could find work: in the mines, in factories as general labor, in the agricultural South, and wherever they found heavy construction across the U.S. Opportunities for women were fewer, limited mostly to work in the needle trades or as proprietors of boardinghouses. Don't limit your search to East Coast big cities.

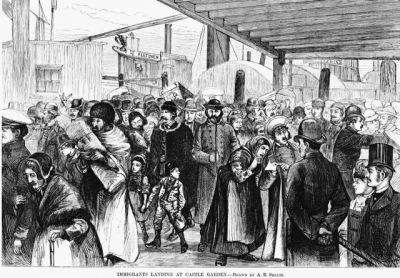

- All came through Ellis Island. Italians arrived at all the major East Coast and Southeast ports of the U.S. Among these, NYC, Boston, Philadelphia, Baltimore, and New Orleans figured chiefly. Ellis Island opened in 1892. Prior to that, Castle Garden received third class immigrants arriving at the Port of New York. Don't limit your search to just Ellis Island records. Ship passenger list databases also exist for other ports of entry.

- All immigrants arriving in the U.S. had to undergo a rigorous inspection process. The great majority of Italians traveled third class (steerage). Upon arrival, they had to submit to a physical and mental examination. In the case of Ellis Island, first and second class disembarked without inspection. There are cases where a husband traveled steerage while the wife went second class. How did your ancestors arrive?

- All Italian immigrants entered with their papers in order. The great majority of Italians bound for U.S. ports entered through normal immigration channels. After the restrictive immigration laws of the early 1920s, it was not unknown for Italians to enter clandestinely at the Mexican and Canadian borders, which at the time were less guarded than today. In 1929, a law of Congress granted legal registry or amnesty to aliens without legal papers if they were of good moral character. If you can't find an ancestor in any of the standard documents, it's possible they arrived illegally. This is especially true of men. Try the research tools available online at the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services website under “Searching the Index.”

- Our names were changed at the port of entry. In the Ellis Island records, there are misspellings of names. This certainly happened more often to Jews, Russians and others whose languages were not written in the Latin alphabet. United States Custom officials did not have the training to transcribe those names, nor did English equivalents even exist in many cases. Consequently, this group of immigrants tended to lose the original spelling of their first and last names as soon as they arrived. Italians, on the other hand, carried documents with full names and other vital information in the Latin alphabet whether they were literate or not. Once in the U.S., many changed their given and surnames because of prejudice or to simply assimilate more easily in their new country. Misspellings in the transcripts of ship manifests are unintentional. There was no official U.S. immigration policy to rename Italians at the various ports of entry.

- They all spoke Italian. The overwhelming majority of immigrants from Italy spoke regional and local languages often called dialects; not standard Italian. Nonetheless, those who were literate attempted to write in the standard language. Keep an eye out for family letters and text written on the back of photos and holiday cards. Expressions in nonstandard Italian offer clues to your ancestor’s native dialect. Find someone to translate the text.

- Everyone's destination was the U.S. As conditions in the southern part of Italy began to worsen after Unification, Italians soon began emigrating. As early as the 1870s, they departed for Brazil, Argentina, Canada, and U.S. ports. You could have cousins living in Buenos Aires, São Paulo or elsewhere in the Western Hemisphere.

- The U.S. welcomed immigrants from Italy. Immigrants from Italy, as well as those from Southern Europe, Ireland and China, provided steady, cheap labor to build industries and infrastructure in the U.S. While the work of these laborers was valued, their presence in the community was often met with hostility and prejudice. Unfamiliar with English, Italians were often used as strikebreakers. Anti-immigrant bias grew throughout the early 1900s and culminated in two acts of Congress, in 1921 and 1924, that severely restricted immigration from Italy and many other countries whose citizens were considered “less desirable.” It was only in 1968, that Congress rescinded those acts. Be aware that the stories our immigrant ancestors handed down often omitted these hard times.

- They all settled in a "little Italy." Foremost on the minds of newcomers was to find work. Consequently, Italians lived close to the place of employment, often side by side with working families of many backgrounds. When searching city directories ("reverse telephone books") don't ignore streets near factories and mines.