The evening of June 29, 1906, a fire broke out in the large factory at the corner of Watt and Boardman Streets in Youngstown. The flames soon lit up the sky, filling the eastside of downtown with smoke. An entire pasta factory was being consumed by the huge blaze. An eyewitness to the conflagration reported that the burning macaroni “presented a beautiful sight.” According to his report, the inventory would “blaze up and develop some temporary etching in flames that could hardly be surpassed by any artist.” The loss to the Youngstown Macaroni Company totaled $50,000 or about $1.5 million today. Valuable Italian-made machinery and extrusion molds figured in the toll of destruction.

News of the plant’s opening had greeted readers of the March 20, 1891 Youngstown Evening Vindicator. V. D. Salvo, Donato Deprimio and Stephan Ross, all grocers on East Federal Street, appear as lease holders of the building. An advertisement for the Youngstown Macaroni Company ran in the same newspaper in 1893. It touts the facility as the first macaroni factory in Youngstown and one which manufactures the varieties used in Naples. In the Vindicator’s “Industrial Supplement” of April 1893 an article extolled the nutritional qualities of the company’s pasta calling the food, “delightful, palatable, easily digestible, healthful, a splendid builder of nerve and sinew tissue and recommended by the leading physicians as an article of food calculated to invigorate, and strengthen those who eat it.”

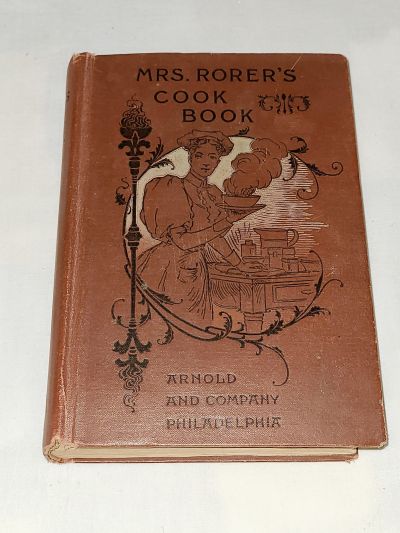

While the production of spaghetti and other cuts of dried pasta was ongoing in the Mahoning Valley, macaroni (the preferred name in those days) was also making a hit in other parts of the U.S. One early recipe appeared in the popular “Mrs. Rorer’s Cookbook” of 1886.

“Macaroni, as an article of food, is rather more valuable than bread, as it contains a larger proportion of gluten. It is the bread of the Italian laborer. In this country it is a sort of luxury among the upper classes; but there is no good reason, considering its price, why it should not enter more extensively into the food of our working classes. ‘Spighetti’ is the most delicate form of macaroni that comes to this country.”

It is interesting that Mrs. Rorer misspelled “spaghetti” and even more so that she identified the dish with social class, the upper and the laboring ones. Her recipe, Macaroni à l’Italienne, bears a French title, a foreign language that seems to turn unassuming things into luxuries; chaise lounge for a “long chair” and cul de sac for “dead end.” The 1886 recipe is really an old Italian favorite, cacio e pepe. Did she affix a French name to the dish to attract middle class readers to her publication?

Mrs. Rorer’s Macaroni à l’Italienne:

1/4 pound of macaroni

1/4 pound of grated cheese

1/2 pint of milk

Butter the size of a walnut

Salt and white pepper to taste.

Break the macaroni in convenient lengths. Put it in a two-quart kettle and nearly fill the kettle with boiling water; add a teaspoonful of salt and boil rapidly twenty-five minutes; then drain; throw into cold water to blanch for ten minutes. Put the milk into a farina boiler; add to it the butter, then the macaroni and cheese; stir until thoroughly heated, add the salt and pepper, and serve.

More recently, the Youngstown Macaroni Company’s Watt Street plant appears as the fictional focus of Adriana Trigiani’s novel “The Supreme Macaroni Company.” In this case, she adapted the name “Supreme” to the location of the 1906 fire. The best-selling author has made repeated trips to the Mahoning Valley, where she gave book talks in Poland, OH and at Our Lady of Mt. Carmel Basilica in 2017.

Though the Youngstown Macaroni Company closed its Chardon, OH plant in 1910, quality dried pasta has continued as one of the staples of the Youngstown diet. Over the years, area wholesalers have made available many brands of Italian style macaroni: Vimco, Romi, Prince, San Giorgio, Gia Russa, Biutoni, Ronzoni, and the popular favorites imported from Italy such as De Cecco, Fara San Martino and Barilla. But I’ll bet that the reigning champions in our area continue to be the humble gnocchi and cavatelli, not mass-produced in a factory but made from scratch by the skillful and loving hands of family members.

Many thanks to Joe Tucciarone and Lori Hildebrand Mallory for help with this article.

https://www.lagazzettaitaliana.com/local-news/9584-pasta-s-early-footprint-in-the-mahoning-valley#sigProId8cf660f74c