“Sir, a man who has not been to Italy is always conscious of an inferiority…”

Samuel Johnson

“In Rome I have found myself for the first time.”

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

“The spectacle of Venice afforded some hours of astonishment and some days of disgust.”

Edward Gibbon

The tradition of the Grand Tour of continental Europe as a “finishing school” for well-born, young men peaked in the years from 1763 to 1796. During a time in their late teens, these individuals from the moneyed, upper classes considered visiting the major art centers of Europe with a tutor or cicerone, a crucial part of a classical education. In later years, participants in the Grand Tour represented a much wider cross-section of both men and women of different ages, backgrounds and social rank. In its purest form, however, the Grand Tour was frequented by young men of means with a thorough grounding in both Greek and Latin literature, an interest in art and need of social and cultural refinement. As a reminder of one’s travels, these Grand Tourists often returned home with souvenirs of their travels that included paintings, sculptures, prints, books, and a host of related antiquities.

The costly and arduous trip could last anywhere from a few months to eight years. London frequently served as the starting point for the journey. Paris might be the next stop. But Italy was the primary destination as young men and their academic guardians concentrated on the art of Venice, Florence, Rome, and Naples.

Taken together, Venice, La Serenissima, and Rome, the Eternal City, represented the highest ideals of both the educational and leisurely pursuits of travel. In Rome, a young student could see and touch the remains of the ancient world, including some of the greatest works of classical architecture and sculpture. Many ancient masterpieces were discovered and written about at the very time Grand Tourists were in the city.

In both Rome and Venice, a seemingly endless array of religious holidays, festivals, celebrations, and spectacles exposed visitors to a variety of local customs, cultures and manners. Many of these pageants and masquerades, most especially Carnival in Venice, became learning grounds of another kind – tied to the dissolute activities and sensual pleasures of the flesh. All these places, events and people became subjects for the many artists whose careers centered on documentation and celebration of the Grand Tour.

Painters and printmakers such as Giovanni Paolo Panini (1691-1765), Hubert Robert (1733-1808), Giovanni Battista Piranesi (1720-78), Canaletto (1697-1768), Francesco Guardi (1712-93), and Antonio Joli (c.1700-77) were commissioned by travelers to record the architectural landmarks and scenic views (vedute) of Rome, Venice and the surrounding countryside (campagna) or to create their own fanciful inventions (capricci). Sculptors like Giacomo (c.1731-85) and Giovanni Zoffoli (1754-1805) fulfilled the demand for small-scale bronze copies of famous antique sculptures to decorate mantelpieces and tables in the homes of Grand Tour travelers.

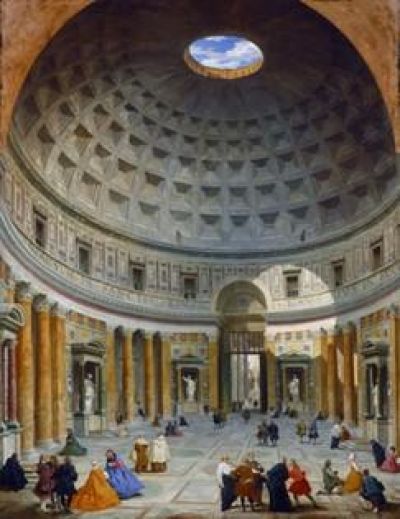

In Panini’s majestic “Interior of the Pantheon” (c.1734), the painter gives us a view of what was already in the 18th century one of Rome’s most visited ancient monuments and one of the world’s most important domed buildings. Panini was among the most accomplished and popular painters of such scenes especially with the English public. His Venetian counterpart, Canaletto, was equally famous and highly regarded by English tourists, most notably the businessman Joseph Smith, who amassed one of the largest and most important collections of the artist’s work.

Piranesi’s evocative prints on Roman themes such as the “Arch of Titus” (1748) and the “Arch of Constantine” (1748) helped to fuel a fascination with the romantic nature of ruins and became emblematic statements on the rise and fall of civilizations. The processions, pageants and regattas depicted in the paintings of Francesco Guardi and Antonio Joli were festive celebrations of contemporary Venice’s continual relationship to the sea.

Portraits of Grand Tourists and of the writers and historians whose works helped to define and to disseminate the idea of a rediscovery of the classical past, as seen in the “Portrait of Johann Winckelmann” (1780) by Angelica Kauffmann (1741-1807), placed human faces on the Grand Tour experience. The humorous caricatures and satirical works of Pier Leone Ghezzi (1674-1755) also brought the people encountered on the Grand Tour to life.

While the nature, goals, scope, and participants of the Grand Tour changed through the years, the abiding allure of Italy would last well into the next century, and down to the present. The past grandeur of Rome and the slowly decaying nature of Venice continued to act as the creative backdrop for a host of artists, poets, writers, and composers, and for all seekers of truth, beauty, and personal awakening.

-

Giovanni Paolo Panini,...

Giovanni Paolo Panini,...

Giovanni Paolo Panini,...

Giovanni Paolo Panini,...

-

Canaletto, “The Square...

Canaletto, “The Square...

Canaletto, “The Square...

Canaletto, “The Square...

https://www.lagazzettaitaliana.com/history-culture/9691-from-la-serenissima-to-the-eternal-city-the-grand-tour-in-18th-century-venice-and-rome#sigProIdd18273c8f1