Intorno alla fine del dicembre 1872, giunse voce agli oltre 530 immigrati italiani bloccati su Ward’s Island nel tentativo di raggiungere l’Argentina, che in varie parti degli Stati Uniti si cercavano operai. In particolare, la Chesapeake e la Ohio Rail Road a Richmond avevano bisogno di assumere uomini forti e desiderosi di iniziare subito a lavorare. Ma come potersi permettere il viaggio per raggiungere il cantiere dove era stato avviato un imponente progetto di costruzione di un tunnel? Dal nulla, arrivò il generoso regalo di una coppia benestante, Egisto Paolo Fabbri e moglie Mary Kealey, residenti a New York, che donarono circa $ 1.000 (circa $ 25.000 oggi) per dare loro modo di acquistare il biglietti del treno per la Virginia.

Imagine that you and your traveling companions have purchased tickets for a faraway retreat and then, at the last minute, the final and most important leg of your destination is canceled by the tourist agency. No refunds will be given and no return trip home provided. You are stranded in a foreign country whose language you cannot speak and where no one in your group has a contact. To boot, it has been announced that your bags did not arrive and never will. It is winter there. As your unpredicted stay lengthens, the natives begin looking at you with suspicion.

Sounds like a nightmare. And it was in late fall of 1872, for hundreds of Italians arriving in New York aboard the S.S. Holland. Some had mortgaged house and farm in Italy to pay passage to South America, where it would be spring. Others had taken out high interest loans. Departing Italy for Argentina in a multi-leg exodus, they envisioned a better life would soon be theirs. At the next to the last stop in NYC, port authorities broke the news that there was no connecting vessel to Buenos Aires and that most of their baggage had gone on. Tickets purchased so dearly in Italy were now worthless. No refund and no assistance for returning home would be given the 532 Italian passengers of the Holland and about 150 fellow passengers of other nationalities. Almost 700 wayfarers found themselves in the port of New York without their luggage, dumped in the wrong city on the wrong continent.

As more ships from Europe arrived that year and the next, numbers of destitute Italians in New York climbed. They and the Holland’s passengers were assigned temporary lodgings on Ward’s Island, the site of a large insane asylum and hospital. New Yorkers were uncomfortable with so many jobless arrivals from southern Europe, double the numbers of a few years ago. Newspaper headlines speculated on what should be done with the Italians whom the papers sometimes painted as outlaws.

Then, in late December, word reached the Italians sheltered on Ward’s Island that employers were seeking laborers in various parts of the U.S. In particular, the Chesapeake and Ohio Rail Road in Richmond needed strong backs, excavators and ditch diggers. But how to pay for transportation to the worksite where a huge tunnel project was ongoing? From out of nowhere, a generous gift appeared from a wealthy couple, Egisto Paolo Fabbri and wife Mary Kealey, residents in NYC. They provided $1,000, about $25,000 today, so that victims of the Holland incident and other stranded Italians could purchase train tickets to the Virginia construction site.

Who were these wealthy benefactors? What can they tell us about the contemporary Italian immigrant community? Before the U.S. Civil War, many Italians living in NYC were artists and professionals, the majority of whom were from central and northern Italy. They helped this growing seaport surpass Philadelphia as the nation’s economic and cultural capital. In the mid-1800s, Mary Kealy Fabbri, a native of England, traveled to America from Italy with her husband Egisto Paolo Fabbri. He was born in Florence, Italy and eventually made his money in New York through shipping and finances. Notably, Egisto was a partner with J. P. Morgan, one of the foremost bankers in the U.S. In 1883, the Fabbri helped found the Metropolitan Opera Company of NYC. Egisto and Mary were members of the Protestant Episcopal Church.

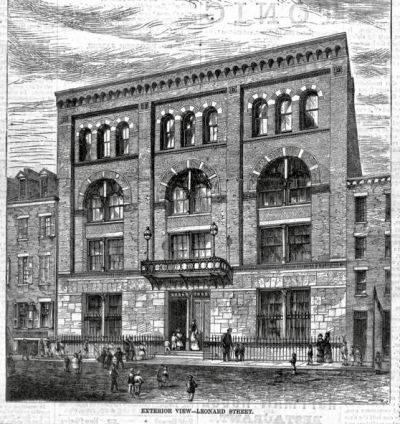

Mention of another Fabbri gift appeared in the illustrated pages of Harper’s Weekly of April 17, 1875. The magazine article recounted the Fabbri’s contribution to the city’s Italian children. The couple, along with the Children’s Aid Society, had organized contributions reaching over $600,000 in today’s dollars to construct the Italian School on Leonard St. in NYC's notorious Five Points neighborhood. The full-page magazine piece informed readers that the four-story, Italian-styled stone edifice housed classrooms, a music hall and other amenities. Amazingly, in an era when indoor plumbing was extremely rare, the school’s washroom and bathing area could accommodate 40 children at a time. Apparently, no expense was spared to equip the Italian School’s new home. Truly, the neighborhood sorely needed it.

Five Points had been an eyesore and public danger for several decades. The area, plagued by overcrowding, infectious diseases and a lack of sanitation, witnessed several murders a week. Perhaps only the poorest, most desperate slums of London could have rivaled Five Points in total urban neglect and crime. Sadly, into the squalor poured many Italians who had bet their life’s savings or had taken out mortgages to begin life anew in America. Between 1872 and 1873, at least 11 ships of destitute Italians disembarked at the nearby Castle Garden immigrant processing center, including the ill-fated passengers of the Holland. This first wave of Italian immigrants had purchased steamship tickets in Italy from agents and local officials who had gleaned thick commissions from the transaction. Five Points was the destination that many had been directed to before they boarded ship.

Was it the plight of needy Italians disembarking in 1872-73 that moved Egisto and Mary, themselves shipping magnates? Or was it the couple’s religious zeal? Did patriotic feelings toward the newly united Italy motivate their philanthropy? No record exists in the Fabbri historical archive to illuminate these questions. What remains is the example of a remarkable couple and their response to the needs of Italians at the beginning of mass immigration to the United States.

https://www.lagazzettaitaliana.com/history-culture/9364-the-gifts-of-the-fabbri#sigProIdd1deb35a0a