Il “Libro delle Ore” comprende la raccolta delle ore liturgiche per i diversi periodi dell’anno e consiste nel canto di salmi, cantici e inni, con l’aggiunta di preghiere e letture dalla Sacra Scrittura. Per secoli, in Europa fu uno dei testi che non mancava presso tutte le famiglie aristocratiche o le comunità che potevano permettersi di avere libri. Ben presto divenne anche un oggetto riccamente miniato, opera di abilissimi artisti italiani e francesi. Il Museo di Arte di Cleveland annovera nella propria collezione del periodo medievale uno degli esempi più magistralmente decorati di libro delle ore, una volta appartenuto al Re Carlo III di Navarra.

Italians have always been great travelers. In the Middle Ages, Italians traveled across Europe as bankers, merchants and businessmen. It is no surprise that Italian artists of the Middle Ages and Renaissance also have a long and distinguished history of traveling to other countries to earn their livelihood, often working for monarchs and noblemen.

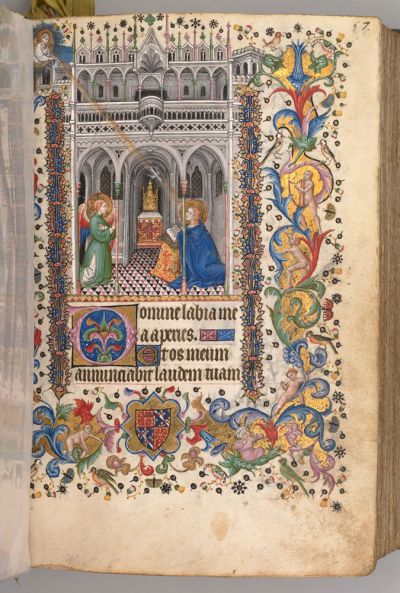

Within the medieval galleries of the Cleveland Museum of Art, a deluxe book of hours once owned by King Charles III of Navarre, also known as “the Noble” will be found. Charles reigned over a small independent kingdom straddling the Pyrenees between northeastern Spain and France from 1387 until 1425. Though Charles the Noble was French-born, his small kingdom of Navarre played a fairly important international role at the time. Its kings had both blood and feudal ties with many other royal houses, most importantly France. Charles is documented as visiting Paris in 1404 and it seems likely that on this occasion he acquired his sumptuous book of hours. His coat of arms, bearing the royal arms of Navarre quartered with those of Évreux, is painted in the lower margin of some 25 folios of the manuscript, indicating that it was highly esteemed by its owner.

In terms of its page layout and overall design, the Hours of Charles the Noble conforms largely to Parisian standards. In 1404, Paris was the center of the European book trade which, perhaps, explains the involvement of Italian illuminators. Though the book is written in Latin, its calendar pages are in French and list the customary Parisian saints. Yet the manuscript is also a work of international scope and points to the cosmopolitan character of the French capital at the beginning of the 15th century. The characteristics of the book’s decoration include courtly elegance and delicate naturalistic detail, features of what art historians call the International Style.

The Hours of Charles the Noble perfectly reflects this artistic milieu in terms of its decoration and style. Though there is a relative aesthetic harmony to the book’s decoration, the illumination is clearly a collaborative effort involving an international team of artists working in the French capital. There is stylistic evidence of at least six illuminators; two Italians, two Parisians and two Netherlanders. We know nothing about the circumstances under which they worked nor how such disparate painters came to work in Paris on a collaborative project. The two Italians contributed most of the volume’s decoration. Stylistically, the Hours of Charles the Noble represents one of the most remarkable fusions of French and Italian taste ever achieved.

The illuminator who planned the decoration of the book, and who produced 17 of its large miniatures, was a Bolognese artist known to art historians as the Master of the Brussels Initials. He was an anonymous illuminator who began his career in the late 1300s in a prominent workshop in Bologna. His name comes from the 15 historiated initials he painted in a book of hours, now in Brussels, commissioned by Jean, duc de Berry.

Also of interest in the Hours of Charles the Noble are the rich marginal decorations painted by our Florentine illuminator, Zecho. Page after page contains rolling multi-colored acanthus leaves with clambering playful drolleries, those hybrid half-human, half-animal figures, some playing musical instruments and some simply making mischief. His palette reveals a combination of colors favored in his native Florence; fuchia pinks, orange and green. The marginal decorations are especially noteworthy for their often humorous, eccentric or plainly irreligious character.

By the early 1400s, books of hours were at their peak of popularity with European aristocrats. They, essentially, comprised texts such as prayers, psalms, antiphons, hymns, and other devotional material arranged around the eight canonical hours. They were the devotional books of the laity. By Charles the Noble’s time, books of hours had become the most prevalent book in the libraries of nobility. They were commonly decorated with a cycle of miniatures and other illuminations according the means of the patron to pay for it.

Charles the Noble was such a patron. He was crowned and later buried in Pamplona Cathedral. He invited French sculptors to decorate the cathedral and commissioned Jeannin Lomme of Tournai to construct an imposing alabaster tomb for him and his wife, Leonora of Castille. With its procession of mourners, it was inspired by the celebrated tomb of the Burgundian duke, Philip the Bold (1364-1404) in the Chartreuse de Champmol near Dijon. Charles also built an imposing palace, the Royal Castle of Olite, located in the center of Navarre and built between 1402 and 1425. The castle stands near the banks of the Rio Aragón and remained the principal residence for Charles and his successors. Charles is said to have been fond of books and owned a library of substantial size with titles ranging from treatises to fables as well as devotional books. Few of these are known to survive save his book of hours now in the museum’s collection. It was at the Royal Castle of Olite, no doubt, that this precious volume was kept and used by the king of Navarre.

Charles died in 1425 and his book eventually continued on its journey to Cleveland. It remains a mystery how the two talented Italian illuminators arrived in Paris and collaborated on a devotional book for a king. It may be assumed that their services and their talents were in demand in a city then teaming with native-born book illuminators.