Before the unification of Italy with Rome as its capitol in 1871, the immigrants who arrived in America were highly skilled in trades admired by the Americans. Italian culture had been embraced by Thomas Jefferson who visited Italy in 1787, long before the schemes of unscrupulous businesses deceived Italian immigrants by promising them riches in America.

In “Italians Swindled to New York: False Promises at the Dawn of Immigration,” Joe Tucciarone and Ben Lariccia uncover the chain of events that led to recruiting and transporting thousands of Italians to America with the false guarantee of employment. The deceit was devised by a network of collaborators – shipping lines, governments, town officials, and local newspapers.

In the Prelude, the authors address the “Political Change and Social Chaos” of the newly formed Kingdom of Italy (in 1861): “At first, the Kingdom of Italy offered little to soften the blow of political and cultural change hitting the South. As a result, emigration increasingly seemed the only hope of escape. Those attempting to leave were overwhelmingly impoverished men who were illiterate, unfamiliar with English and did not speak standard Italian.”

In providing historical facts obtained through government records, newspaper archives, libraries, historical societies, cultural institutions, and genealogy records, the authors expertly answer the question they ask: “What was happening in newly united Italy that motivated Italians to depart for northern Europe and the Americas?” While Italy was experiencing internal strife, the news was traveling across the Atlantic. They note: “As immigration from Italy increased in the early 1870s, the American reading public followed these accounts of widespread disorder taking place in the former Bourbon kingdom. Increasingly, Americans wondered how the United States would assimilate the oddly foreign Italians, economic refugees now spilling into the Port of New York.”

In the section of the book titled “Deception,” the authors explain how the swindle started, what the U.S. and Italian governments were doing to address the problem, and the “Growing Contention between Capital and Labor.” They write: “The Civil War spurred the growth of industry and mining, with workers gaining advantage because of the huge demand for war materials. Not surprisingly, the early 1870s saw increased contention between labor and capital, as rank-and-file workers clamored for improved working conditions …”

The conflicts between labor and management eventually resulted in the acceptance of the eight-hour workday, but strikes were common, and immigrants provided an easy solution to the labor problem: “The recruitment of Italian immigrants as coal miners marks a controversial and turbulent chapter in the history of their integration into American society. Unfortunately, their initial enlistments appear as strikebreakers. This bred hostility and resentment among their American counterparts…”

The third section, “Legacy,” exposes work violations and the working environment for Italian immigrants: “Economies of scale in construction and other industries led to the proliferation of Italian work gangs in the 1880s. Food and housing were cheaper for a large group of hands…Moreover, managers of Italian workers almost always underbid other contractors when competing for jobs. As a result, teams of Italians were readily employed at trades where sizable numbers of men were needed…public works, iron mills and coal mines, but they were particularly evident on railroad projects…” Through Congress’s continued investigations into labor exploitation, stronger labor and immigration laws were enacted, but it took years before they were enforced.

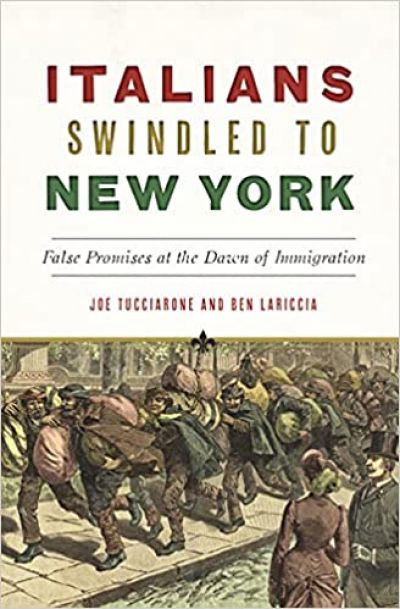

Enhanced with sketches, pictures and graphs that not only support the content of “Italians Swindled to New York: False Promises at the Dawn of Immigration,” but also add visual interest. An Epilogue, Appendixes, Notes, and an Index further supplement the material provided and show the extent of research by the authors.

As with their previous book “Coal War in the Mahoning Valley: The Origin of Greater Youngstown’s Italians,” this book addresses an important element of Italian American history that has been overlooked. It is a thought-provoking study of Italian immigration to America, and a compelling addition to private or public Italian American libraries and any library of American history.